Modern organizations are moving fast across the business landscape amidst international tensions and challenges imposed by today's markets. Economic slowdowns and increasing geopolitical instabilities create the ideal scenario for digital adversaries to quickly position themselves and gain global visibility, creating the instability, uncertainty, and chaos that organizations fall into when they are victimized by deliberate counteractions.

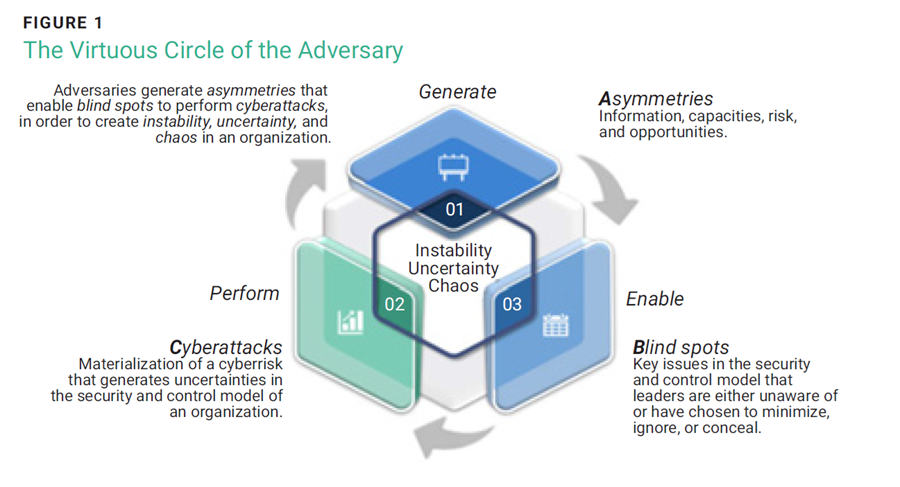

As such, enterprises must recognize and understand the virtuous circle of attackers, wherein adversaries generate asymmetries that create blind spots and enable cyberattacks, resulting in instability, uncertainty, and chaos across an organization. This understanding allows organizations to step beyond the safety of established standards and best practices and develop new defense capabilities. While implementing these practices is necessary to address risk, it is equally important to complement them in light of current uncertainties. The growing complexity of digital solutions necessitates greater interconnection and coupling between different components in a digital ecosystem.

The objective of digital adversaries is to evade detection by the surveillance systems and safeguards implemented by organizations. Bypassing detection allows them to effectively carry out their intelligence process and position their strategies in the technological infrastructures of target organizations. From there, these adversaries create the necessary uncertainties to disrupt cybersecurity teams, establish the conditions of instability, and act accordingly.

Facing modern digital adversaries implies mobilizing efforts and replacing the protection and assurance paradigm that has worked until today with one that explores uncertainty, adapts amid instability, and learns from adversarial behaviors and events. Thus, the familiar exercise based on the US National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST's) stages (Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, and Recover),1 which assumes a victim position, must move toward a more proactive and prospective position that develops intelligence based on data from the environment and adversary behaviors, while increasing the resilience of the enterprise in the face of an adverse event.

It is worth reviewing in detail the attackers' virtuous circle, which starts with the generation of asymmetries in four domains: information, capabilities, risk, and opportunities. There are potential blind spots that may arise within an organization’s security and control model due to these asymmetries. Cyberattacks exploit these identified blind spots, leading to uncertainty, instability, and chaos within organizations. To best understand these concepts, it can be valuable to review the traditional view of security, the virtuous circle, and ways to face and respond to adversary dynamics.

As long as organizations rely on standards and good practices only, and do not embark on facing the uncertainty involved in the governance and management of cyberrisk, there will be more room for adversaries to create zones of uncertainty, instability, and chaos to capitalize on their interests.Traditional Cyberrisk Management—Victim Posture

Organizations currently treat cyberrisk in a manner equivalent to information and communication technology (ICT) risk, which leads to the creation of blind spots, i.e., key issues in the security and control model that leaders are unaware of or have chosen to downplay, ignore, or hide. IT risk is a known risk that has a concrete framework to secure an organization and reduce cost. Cyberrisk, a systemic and often unpredictable threat, poses a significant challenge. The challenge with cyberrisk does not lie only in business continuity, but also in the resilience of the business.

In this sense, organizations maintain a victim posture where they remain waiting for an attack at all times. To prepare for an attack, organizations frequently consult the general doctrine of cybersecurity established by the NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF). These organizations often overlook the need to investigate and understand the environment, and the intentions and abilities of their adversaries. This understanding is crucial for altering and diminishing the strategic advantage of their attackers.

In this context, organizations develop and maintain a passive posture that seeks to ensure regulatory compliance, which does not allow them to develop activities or actions other than certifying the effectiveness of controls and their adequate reporting to supervisors. This posture maintains the enterprise’s comfort zone and enables adversaries to generate new attacks, which end up compromising the designed controls because they operate outside of the controls, challenging their level of reliability.2

While traditional safety and control frameworks, such as those outlined in International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards, are crucial for addressing known risk, it is equally important to maintain the required level of calibration. That is, establish a routine review and analysis of the sensitivity of the control as a sensor. This involves challenging its basic specification and the history of its effectiveness in such a way that, despite the changes and adjustments that are made in the organization, the sensor continues to measure what is important and respond to the known events and threats for which it was designed.3

As long as organizations rely on standards and good practices only, and do not embark on facing the uncertainty involved in the governance and management of cyberrisk, there will be more room for adversaries to create zones of uncertainty, instability, and chaos to capitalize on their interests. This may generate a misinterpretation of the hard work of cybersecurity teams. Their management may face constant scrutiny, necessitating frequent explanations whenever an adverse event occurs within the enterprise.

The Adversary's Virtuous Circle—Asymmetries, Blind Spots, and Cyberattacks

It is not common to speak of a virtuous circle for an adversary, as the focus is typically on the efforts of cybersecurity analysts to maintain the peace of mind and certainty that executives demand. Generally, important investments are made for which results are expected.

Nothing could be further from reality than the expectation that many executives have about cyberrisk management: 100% security and zero risk. Neither of these two conditions exist, nor will they exist in the future. The practice of cybersecurity demands an exercise in building and testing operational thresholds when security efforts do not go as planned. In this sense, studying attackers’ virtuous circle provides an alternative view to recognize its key aspects. This understanding can help shape the governance and risk management strategies that respond to the challenges posed by adversaries.

Asymmetries

The virtuous circle begins with the generation of asymmetry at four levels: information, capabilities, risk, and opportunities. These asymmetries, or unprecedented readings generated by the attacker on the organization and its resources, create a zone of uncertainty and low visibility that leads not only those in charge of cybersecurity to try to identify possible attack routes but may also distract them from key aspects that require their attention, such as training executives on cyberrisk issues or improving the organizational culture of information security. There are four types of asymmetries:4

- Information asymmetry—The adversary possesses a greater understanding of the target technology infrastructure than the organization.

- Asymmetry of capabilities—The adversary knows better than the organization what amount of time and resources are needed to access the target (and conduct follow-up activities [e.g., identification of recent vulnerabilities, patches not applied, ]).

- Risk asymmetry—The adversary has a greater understanding of the risk involved in conducting certain cybersecurity operations compared to the organization.

- Asymmetry of opportunity—The adversary has a greater understanding of the information it can acquire and/or the capacity for disruption, denial, degradation, and destruction compared to the organization.

Asymmetries highlight the disruptive capabilities that adversaries can develop through their comprehensive understanding of the environment. This is further amplified by the collaborative networks they generate within a support ecosystem and the coordination of different actors to generate instability, uncertainty, and chaos within target organizations.

Blind Spots

Blind spots are key issues in the safety and control model of which leaders are unaware or have chosen to downplay, ignore, or hide.5 These points are generated by overconfidence in current controls, implemented safety technologies, and recent successes in identifying and controlling adverse events that were previously unsuccessful.

Blind spots usually respond to the manifestation of biases present in the organization’s executives, cybersecurity professionals, and organizational collaborators. This often leads to a false sense of security, culminating in the creation of a window of vulnerability that is built into the dynamics of the organization, and the need to ensure the expected economic results. The establishment of a bias in the interpretation of cyberrisk creates the illusion of control. This illusory control is often challenged by the materialization of an incident that takes all the participants of the organization beyond their comfort zone. It disrupts expected control expectations, and leads to the deterioration of the organization’s trust and reputation.6

Some of the biases of which organizations should be aware are:7

- Underestimation—"That is not going to me."

- Avoidance—"If it happens, it will not happen to me. "

- Optimism—"If it happens to me, it will not be so bad. "

- Acceptance—"If it happens to me and it is bad, there is nothing I can do."

- Denial—"This will not happen again. "

Cyberattacks

A successful cyberattack can be defined as “The concrete way in which an aggressor materializes a threat in a specific context with adverse effects, through the use, exploration, combination, and creation of vulnerabilities and flaws in people, processes, technologies and regulations to generate uncertainty in the security and control models available in an organization or nation.”8

The challenge, more than the failure, the loss of the operation, the effect on infrastructure, or the generation of false information, is the impact both inside and outside of the organization. Internal impacts include compromised organizational culture and the resulting vulnerability and uncertainty among employees. External stakeholders are affected by the erosion of the organization’s reputation and feelings of instability. If the organization is not prepared to face an adverse event, the consequences—economic, social, political, or environmental—generated by its different stakeholders will end up deteriorating the confidence in the organization, ultimately placing the organization in an adverse position that will be interpreted negatively by the markets.

Thus, a successful cyberattack is usually the result of exploiting blind spots in security and control models, which, assisted by the illusion of control, create the perfect scenario for the adversary to notice what is invisible to the organization's security management. In this way, adversaries can surprise organizations in their operations. For example, adversaries can potentially mimic the dynamics of an organization's controls in order to go unnoticed given the low level of control calibration.

Once an attack occurs, it creates new imbalances. These imbalances then restart the cycle, leading to a continuous increase in the attacker’s knowledge. This knowledge allows the attacker to keep their actions unpredictable, reducing the organization’s ability to respond effectively. If the organization recognizes this cycle and the permanent intentions of the adversary, it is possible to respond proactively and prospectively to move from a scheme of protection and assurance (properly calibrated) to one of defense and anticipation that responds to the permanent challenge of the attacker. A summary view can be seen in figure 1.

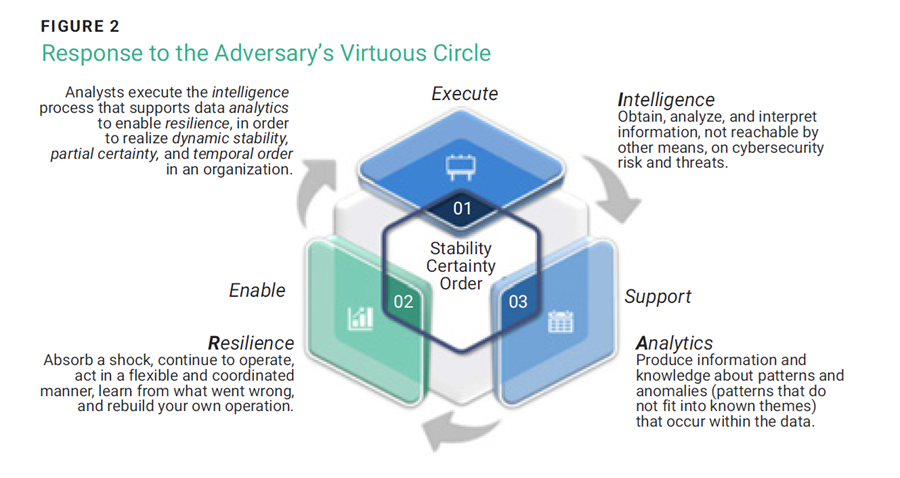

Responding to the Adversary's Virtuous Circle—Intelligence, Analytics, and Resilience

When an organization recognizes the attacker's virtuous circle, it knows that it must update its way of understanding and mitigating cyberrisk. It is not only up to the cybersecurity executive to make the necessary adjustments to maintain security, but also to the board of directors to update its understanding and vigilance of risk, given that it requires a review of the threats and their possible effects on the organization they are part of.

In response to the attacker's virtuous circle, enterprises are preparing to implement three equivalent and demanding strategies (in terms of time, effort, and resources) that will enable them to confront and overcome the competitive advantage built by the adversary. To this end, the concepts of intelligence, analytics, and resilience are incorporated into the management of this risk, not only to protect the value of the enterprise but to also create value and accompany the organization's goals.

Intelligence

Intelligence can be defined as, “The process of obtaining, analyzing and interpreting information, not attainable by other means, on the risks and threats to cybersecurity and the various opportunities for action existing in this area, to produce knowledge (intelligence) that supplies the organization, in order to enable decision-making and make possible the prevention and deactivation of the former and the exploitation of the latter.”9

Decision makers, including senior management and risk owners, must continuously apply this process in cyberrisk management to anticipate new changes in the risk landscape and make timely and informed decisions on the strategy and challenges imposed by emerging cyberrisk. Following the guidelines of ISO 31050,10 the organization must articulate two interactive cycles, an external cycle of exploration of multiple contexts, and an internal one, associated with risk intelligence.

The external cycle seeks to identify small changes in data, circumstances, or behaviors, the intervals in which such changes occur, their implications, and possible effects on the organization and its objectives. This means that managing cyberrisk involves the observation of global geopolitical tensions and their impact on cyberspace. These observations help organizations understand the cyberoperations conducted by international political agendas and the conflicts that arise from the power struggles and influence of different nations.

In the internal cycle, there are four stages:11

- Framing—Defines the scope of cyberrisk, what the organization wants to know, how and why it will learn it, and its alignment with the business objectives

- Collecting and analyzing information—Establishes the identification and selection of information sources, validating their quality and quantity, and revealing patterns (of known threats, anomalies, or oddities) available for analysis

- Interpreting information—Seeks to discover weak signals (i.e., indicators of a potential pattern that may become significant in the ) amid changing circumstances and contexts, as well as the presence of potential emerging issues that generate novel knowledge, leading to the development of plausible scenarios

- Communicating intelligence—Involves how the knowledge developed explains the theoretical and practical aspects that contribute to unexpected changes in an organizational context and how emerging problems can become risk

The internal cycle involves generating more knowledge for the organization and the permanent discovery of emerging cyberthreats that must be analyzed in the context of organizational objectives. In other words, this involves updating the organization's risk map, creating knowledge that was not previously available, and accumulating reusable experiences that can be learned from for the future.12 Thus, when something novel occurs, it presents an opportunity to challenge existing knowledge and opens a new avenue for learning. This process generates an advantageous imbalance for the organization, simultaneously diminishing the adversary's competitive advantage.

Analytics

Many organizations utilize local or third-party- based platforms equipped with monitoring and management capabilities designed to record and report on the status of the security of an organization, including how it has been handling both alerts and alarms that arise in the process of safeguarding events. These events are known and validated through patterns or signatures previously verified and recognized by the suppliers of current security and control products.

This monitoring exercise allows organizations to not only receive notifications of known issues, but also produce information and knowledge about patterns and anomalies (patterns that do not fit into the known issues) that arise within the data. To the extent that the organization can connect the different data sources, ensure their quality, and enhance their use to observe what is latent in the dynamics of the cybersecurity strategy, it will be able to increase the visibility of its potential vulnerabilities and warn the organization of blind spots in the infrastructure or information security architecture.

While the attacker pursues anonymity in the execution of their strategies, the organization must increase not only its ability to analyze and reveal anomalies but also refine the sensitivity of their detection with available intelligence information to increase the visibility of the attackers' actions and their possible targets. This ensures that monitoring is strategically designed and tailored to assess the capabilities of adversaries and thus adjust the available security and control mechanisms based on the trends identified in real time.

This implies a radical change in the use and exploitation of the data produced by security platforms. Traditionally, these platforms have served as repositories of evidence of past events that end in the confirmation of indicators of compromise. This approach is crucial to maintain a detection posture. However, currently, the challenge is to sense and respond to events or unusual situations that can be identified on account of the analysis of available information. This information comes from both internal monitoring logs and those provided by specialized third parties. Here artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) algorithms play a fundamental role in maintaining an up-to-date view of the situation to make the decisions required. By detecting and evaluating anomalies or unknown threats that generate early warnings, AI and ML algorithms prompt organizations to refine and calibrate their controls.

Resilience

While the integration of intelligence and analytics bolsters the capabilities of the organization to shift the balance in its favor and illuminates possible blind spots, it is clear that failure is inevitable and a cybersecurity incident will come sooner or later. In this sense, the organization must be prepared to face and overcome any adverse cyberevent. This preparedness should include relevant projections of potential effects on the organization’s value promise and even its stock value, as has happened recently.14

Resilience refers to the capacity of an organization to: continue operating during an adverse event, remain flexible and coordinated both internally and with its stakeholders, learn from what went wrong, and recompose its operation and infrastructure to emerge stronger from the situation that exposed it. To the extent that an enterprise manages to recognize in its security model the principle of “vulnerability by default,”15 it knows that it must work to have the asymmetries in its favor and, above all, recognize the level of exploitability of its vulnerabilities.

There are several approaches to accompany and develop cyberresilience in organizations. One such approach, the FLEXI model,16 suggests a simplified view of cyberresilience that allows the enterprise space for conversation around specific adverse events. This view reveals what is not foreseen, how to learn quickly from what is outside of procedures, how to understand and manage the feelings generated by the adverse event, motivate the creation and practice of playbooks, establish communication and coordination strategies, and finally identify tools, processes, etc., that could have been implemented differently.

The complexity of cyberattacks is not solely defined by the damage they inflict or the media attention they garner but by their capacity to generate incidents, instability, and chaos that end up deteriorating the organization’s trust in its employees, and the projection of that same feeling in the different stakeholders. The more mature the executive team is in the governance and management of cyberrisk in an organization, the greater the resilience that can be developed. This leads to a better response to attacks that grants peace of mind and support to both customers and the market where the organization operates in general.

Resilience is not security. While resilience deals directly with uncertainties, security focuses on certainties. In this sense, emerging cyberthreats should be used as the base inputs for cyberresilience reflections. By acknowledging these threats, organizations can proactively design strategies and defenses, transforming potential vulnerabilities into strengths. It is from the discomfort of instabilities and potential adverse geopolitical conditions that enterprises build their competitive advantages. They should be ready to navigate several types of cyber rogue waves:17

- Dynamic (with changing probabilities)

- Asymmetric (impacting different stakeholders)

- Asynchronous (impacting stakeholders at different times)

- Temporal events (with transitory impacts)

An example of a cyber rogue wave may be a cyberpandemic or global cyberwar. Thus, after overcoming an adverse cyberevent in a planned and orderly manner, including lessons learned and a review of the challenges posed by the new normal of the organization, intelligence information is fed and complemented again. This starts a new upward cycle of learning wherein the organization remains out of its comfort zone, knowing that it must take a risk and try to surprise the adversary in its domain.

In short, the organization executes the threat intelligence process that supports data and behavioral analytics. This process, applied to events across different enterprise platforms, fosters the cyberresilience necessary to face unpredictable events. The ultimate goals are to maintain the dynamic stability of business processes, establish a degree of certainty regarding the inevitability of failure, and ensure a sense of temporal order even after a successful action by an adversary. A summary view of this process can be seen in figure 2.

Conclusion

Recognizing the resources and details of the adversary’s virtuous circle enables organizations to be more vigilant and adaptive, through the development of intelligence processes, data and behavior analytics, and resilient capabilities. In this sense, enterprises must start designing a defense ecosystem that transforms the individual efforts of organizations into extended and articulated capabilities that enable forceful responses to adversaries’ proposals of instability.

This defense ecosystem will need to balance the complexity (number and diversity of participants, the sophistication and interoperability of available capabilities, and the scope and nature of relationships: collaboration, cooperation, or integration) and the necessary orchestration (degree of influence of one organization over others, the formality of interactions, and the degree of enforceability and compliance)18 that will enable all participants to realize maximum value in the exercise of defense and anticipation against adversarial strategies as well as impair the attacker's expectations and objectives, thwarting their strategic agenda.

This implies reimagining the challenge of cyberdefense for organizations, which involves:19

- Shifting the traditional mindset of organizations from one based on known risk management to one based on latent and emerging risk that keeps executives out of the comfort zone of zero risk and 100% safety

- Making the right connections with key organizations and strategic third parties to incorporate novel and distinctive capabilities that generate synergies to deter, delay, and distract different adversaries

- Combining defense strategy with business strategy, prototyping and testing possibilities of new technologies, and anticipating emerging threats while maintaining adequate technical and operational flexibility, to surprise the adversary in their territory

Currently, cybersecurity executives who are aware of the challenges and risk involved in the successful operation of the adversary's virtuous circle should:20

- Pay attention to weak signals in the environment.

- Collaborate promptly across the digital and defense ecosystem before emerging threats and relevant opportunities have been revealed.

- Understand the danger of management's strategic assumptions quickly becoming invalid to enable preparedness for adverse cyberevents.

- Reduce the dangers of groupthink by ensuring that all opinions from appropriate sources are heard and taken into account.

- Motivate courageous and collaborative conversations with a proactive and resilient approach to address blind spots in the organization's security and control model.

Anticipating the adversary's movements by following its virtuous circle implies producing early warnings. This process includes risk and opportunities analysis facilitated by detecting weak signals, patterns, and trends. These insights should be incorporated into the threat intelligence process to outline the adversary's challenges, which can be made tangible through the use of scenarios, simulations, and prototypes. Through this approach, it is possible to unlock new learning opportunities that enable the organization to test various approaches utilized by adversaries. This exploration will foster a more proactive and resilient defense strategy, promoting a collective rather than individual future. The result is an articulate and cohesive cyberdefense strategy.

Endnotes

1 National Institute of Standards and Technology, The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 0, USA, 2024, https://www.nist.gov/cyberframework

2 Cano, J.; “Security Risk Management and Cybersecurity: From the Victim or From the Adversary?,” Advanced Sciences and Technologies for Security Applications, 2023, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-20160-8_1#

3 Cano, ; “The Illusion of Control and the Challenge of an Adaptable Digital Enterprise,” ISACA®Journal, vol. 3, 2023, https://www.isaca.org/resources/isaca-journal/issues

4 Smeets, M.; No Shortcuts. Why States Struggle to Develop a Military Cyber-Force, Oxford University Press, 2022, USA

5 DeLoach, ; “Blind Spots in the Boardroom,” NACD Blog, 5 December 2023, https://www.nacdonline.org/all-governance/governance-resources/directorship-magazine/online-exclusives/2023/December2023/blindspots-in-the-boardroom/

6 Op cit Cano; “The Illusion of Control and the Challenge of an Adaptable Digital Enterprise

7 McNulty, E.; “To See the Future More Clearly, Find Your Blind Spots,” Strategy+Business, 7 January 2021, https://www.strategy-business.com/blog/To-see-the-future-more-clearly-find-your-blind-spots

8 Cano, ; ”ADAM Model. A Conceptual Strategy to Rethink Digital Attacks and Update Current Security and Control Strategies,” Global Strategy, no. 22, 18 May 2021, https://global-strategy.org/modelo-adam-una-estrategia-conceptual-para-repensar-los-ataques-digitales-y-actualizar-las-estrategias-de-seguridad-y-control-vigente/

9 Jimenez, ; Manual de Inteligencia y Contrainteligencia (Intelligence and Counterintelligence Manual), CISDE, Spain, 2019

10 International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/Technical Committee (TC), ISO/TS 31050:2023 Risk Management—Guidelines for Managing an Emerging Risk to Enhance Resilience, Switzerland, 2023, https://www.iso.org/standard/54224.html

11Ibid.

12 Martinez, ; “Being Optimistic is Smarter (Being Pessimistic is Easier),” Javier Martinez Intelligent Organizations, 3 January 2023, http://www.javiermartinezaldanondo.com/n200-ser-optimista-es-mas-inteligente-ser-pesimista-es-mas-facil/

13 Benjamins, R.; A Data-Driven Company: 21 Lessons for Large Organizations to Create Value from AI, LID Publishing, 2021, United Kingdom

14 Media, T.; “The Clorox Company’s 2023 Cyberattack: Major Fallout, System Disruptions & Product Shortages,” ThriveDX, 10 November 2023

15 Cano, J.; “PERIL Model. Rethinking Information Security Governance from the Inevitability of Failure,” Memorias Congreso Iberoamericano de Seguridad Informática 2015

16 Cano, J.; “FLEXI - A Conceptual Model for Enterprise Cyber Resilience,” Procedia Computer Science, vol. 219, 2023, p. 11-19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2023.01.258

17 Brill, J.; Rogue Waves: Future-Proof Your Business to Survive & Profit From Radical Change, McGraw Hill, USA, 2021

18 IBM, “The New Age of Ecosystems: Redefining Partnering in an Ecosystem Environment,” 23 July 2014, https://www.ibm.com/thought-leadership/institute-business-value/en-us/report/ecosystem-partnering

19 Ibid.

20 Op cit Deloach

Jeimy J. Cano M., PH.D., ED.D., CFE, CICA

Has more than 28 years of experience as an executive, academic, and professional in information security, cybersecurity, computer forensics, digital crime, and IT auditing. In 2023 he received the ISACA Educational Excellence Award and in 2016 he was named Cybersecurity Educator of the Year for Latin America by the Cybersecurity Excellence Awards. He has published more than 250 articles in various journals and presented papers at industry events internationally.