There is a story, probably apocryphal, that Michelangelo was asked how to carve an elephant. He replied that he would take a large block of stone and carve away everything that was not an elephant. Of course, Mike was making a few assumptions: that he had a big piece of stone to work with, that the stone had no internal flaws that would cause it to crumble, and that everything that was not an elephant had no further value.

I am using this anecdote as a metaphor for Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA). In the past few articles in this space,1 I have spoken highly of ZTA, concluding that “although ZTA is not the end of the progress of information security, and other architectures may still be developed, I do think that ZTA is the best we have today and that it points the way for any future progress.”2 It is based on core principles of least privilege, network segmentation, continuous monitoring and validation, and the prohibition of lateral movement. But as with Michelangelo’s elephant, it is based on certain assumptions.

Policies

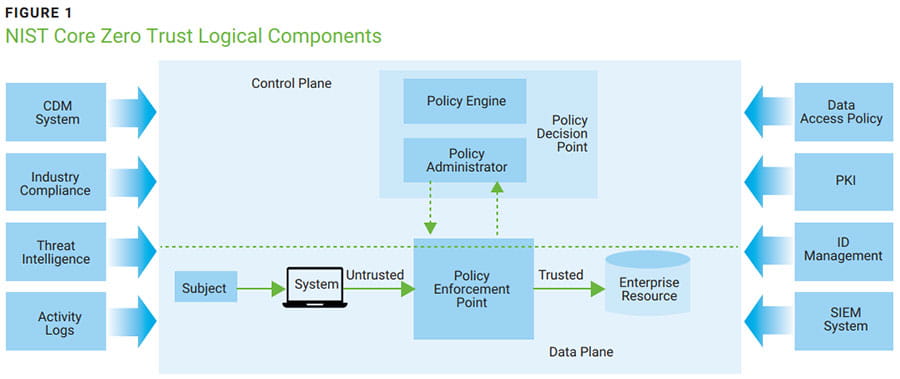

In the US National Institute of Standards (NIST) publication on Zero Trust Architecture,3 there is a diagram that has been widely reproduced as the definitive encapsulation of ZTA (figure 1). In the middle of the diagram are the Policy Engine, the Policy Administrator, and the Policy Enforcement Point, all of which presuppose the existence of policies. Sure, many organizations have security policies, but I question whether they are stated in a way that makes sense within ZTA. If these policies refer to what users, as a group, should or must (or not) have and do, then they cannot be interpreted within the meaning of ZTA. Rather, enterprises need to develop and maintain dynamic risk-based policies for resource access and set up a system to ensure that these policies are enforced for resource access requests, individual by individual.4

Source: Rose, S.; Borchert, O.; et al; NIST Special Publication 800-207, Zero Trust Architecture, National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), USA, August 2020, https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.800-207

These policies do not just come about organically. They require management, both in IT and in business functions, to make conscious decisions as to who—person by person—needs to have access to specified resources in order to perform his or her assigned duties.

Enterprises need to develop and maintain dynamic risk-based policies for resource access and set up a system to ensure that these policies are enforced for resource access requests, individual by individual.RBAC

These managers may choose to create policies at a higher level by grouping individuals with like access requirements into groups, identified by the roles they perform. While numerous commentators have seen the utility of Role Based Access Control (RBAC) in ZTA,5 the actual guidance from NIST states, “A collection of privileges given to multiple subjects could be thought of as a role, but privileges should be assigned to a subject on an individual basis and not simply because they may fit into a particular role in the organization.”6

To my way of thinking, this statement is just silly. RBAC does not make any resource more secure, but it does make the administration (or orchestration, if one prefers) of security more efficient, thereby mitigating the possibility of error in the assignment of access privileges. There are enterprises with thousands of personnel. Making access decisions on a case-by-case basis only prevents someone from doing his or her job or, worse, allows someone access to resources one should not have.

Identity Management

However privileges may be assigned, users have to sign on and access resources on an individual basis. Limiting what each user can access is clearly a part of ZTA; in fact it is the very core of the methodology. The assumption is that those granting access know who the person so granted is actually who he or she purports to be.

An organization may hire someone named Steven Ross, but is he the cabaret singer, the founder of Time Warner, or that security geek in New York?7 If the answer is not conclusively known, why is he being given access at all?

If organizations are serious about limiting access to known and trusted individuals, they need to know who they are dealing with. Usually, verification of identity requires the presentation of documented credentials, such as a birth certificate or a driver’s license. However, anyone can obtain my birth certificate for a small fee plus further identifying documents, which might include a school identification card, a life insurance policy, and a health insurance card with my name on them.8

A bad guy with reasonable technical skills would not be deterred by these restrictions if he really wanted to penetrate an organization’s IT department. If that enterprise is serious about access control, it also needs to be attentive to identity management, requiring background checks and visual identification before placing someone into a sensitive position.

Key Management

While access management is a part of ZTA, identity management is not. Similarly, encryption is a definite part of the architecture, but its enabler, key management, is not explicitly mentioned. This is not the place for a tutorial on cryptography, so suffice it to say that the algorithms are generalized but the keys must be unique to those authorized to encrypt and decrypt data. By extension, therefore, encryption keys are value-added identifiers. Anyone who can decrypt the data must have the key and is therefore authorized to do so. Yes, there is a logical flaw to this statement, but in practical terms that is how encryption keys are used.

Note that the components I have highlighted here—policies, RBAC, identity management, key management—are external to the core process of ZTA as shown in the NIST diagram, or are not mentioned at all. I do not consider this to be a shortcoming of the architecture, but rather a set of conditions that can be assumed to be present in order to make ZTA feasible. By analogy, cars run on gasoline (well, most of them do). Thus, the mechanics of making a car go require systems that deliver gasoline into the engine. It is simply assumed that there will be gas stations to put the fuel into the tank.

Taken together, the architecture and everything that must be there to support it constitute the Zero Trust Environment. I urge readers to consider the environment in its totality because trying to proceed with implementing ZTA without the rest will only impede progress. The interoperability of ZTA-enabled hardware and software can only be accomplished with recognition of the underlying assumptions that are the environment for implementation. Policy cannot be enforced if there is no policy. Users’ access cannot be limited if the users are unknown and their privileges are undefined. Encrypted data is of no use if it cannot be decrypted.9

In other words, the design and implementation of ZTA-based security requires more than the architecture. It calls for the environment as well.

Endnotes

1 Ross, S.; “Who Put the Zero in Zero Trust?,” ISACA® Journal, vol. 1, 2024, https://www.isaca.org/resources/isaca-journal/issues/2024/volume-1/who-put-the-zero-in-zero-trust; Ross, S.; “Information Security Architecture—From Access Paths to Zero Trust,” ISACA Journal, vol. 2, 2024, https://www.isaca.org/resources/isaca-journal/issues/2024/volume-2/information-security-architecture; Ross, S.; “The Inhibitors to Zero Trust Architecture,” ISACA Journal, vol. 3, 2024, https://www.isaca.org/resources/isaca-journal/issues/2024/volume-3/the-inhibitors-to-zero-trust-architecture

2 Op cit Ross “Information Security Architecture—From Access Paths to Zero Trust”

3 Rose, S.; Borchert, O.; et al; NIST Special Publication 800-207, Zero Trust Architecture, National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), USA, August 2020, https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.800-207

4 Ibid.

5 One, chosen almost at random is, Malcomb, P.; “Zero-Trust Access Controls: Trust but Verify,” Retail & Hospitality ISAC, 20 December 2022, https://rhisac.org/zero-trust/zero-trust-access-controls/. He says, “Leveraging RBAC-style profiling can assist with identifying the highest-risk accounts and can, if properly implemented, significantly reduce the quantity of overly permissive accounts if properly designed and implemented.”

6 Op cit Rose

7 I have a lifetime of stories to tell about the number of times I have been misidentified as some other Steven J. Ross.

8 Virginia Department of Health, “ID Requirements,” USA, https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/vital-records/id-requirements/

9 Alas, the bad guys who issue ransomware have figured this out as well.

STEVEN J. ROSS | CISA, CDPSE, AFBCI, MBCP

Is executive principal of Risk Masters International LLC. He has been writing one of the Journal’s most popular columns since 1998. Ross was inducted into the ISACA® Hall of Fame in 2022. He can be reached at stross@riskmastersintl.com.