Unfettered access to private consumer data has enabled some organizations to mismanage the use, storage, and transfer of that data.1 This has driven lawmakers to create and implement data collection and privacy laws and policies. One of the most comprehensive of these laws is the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which was established in May 2018.2 Since then, many other countries and regulatory authorities have implemented data protection legislation.3

The growing body of regulations makes data collection and data protection compliance complex objectives for many organizations. What is clear is that enterprises are being held accountable for their use, misuse, or mismanagement of personal data. Fortunately, an accountability approach to data can help organizations ensure that sensitive data is protected and compliant with evolving regulations.

GDPR Background and Purpose

The GDPR set a global benchmark as the toughest privacy and security regulation the world had ever seen.4 It is a wide-ranging regulation that addresses the use of personal data, which is defined as all information that identifies a living individual.5 Included in the regulation is the implied requirement to implement data protection by design and by default across all organizational actions.6 The 88-page regulation goes on to state potential violations, fines, and enforcement protocols.

Reviewing GDPR fines offers valuable insight into the state of privacy compliance. These insights, when viewed through the lens of accountability, can equip organizations with a roadmap for compliance with current and future data collection and usage regulations.

GDPR Violations and Fines

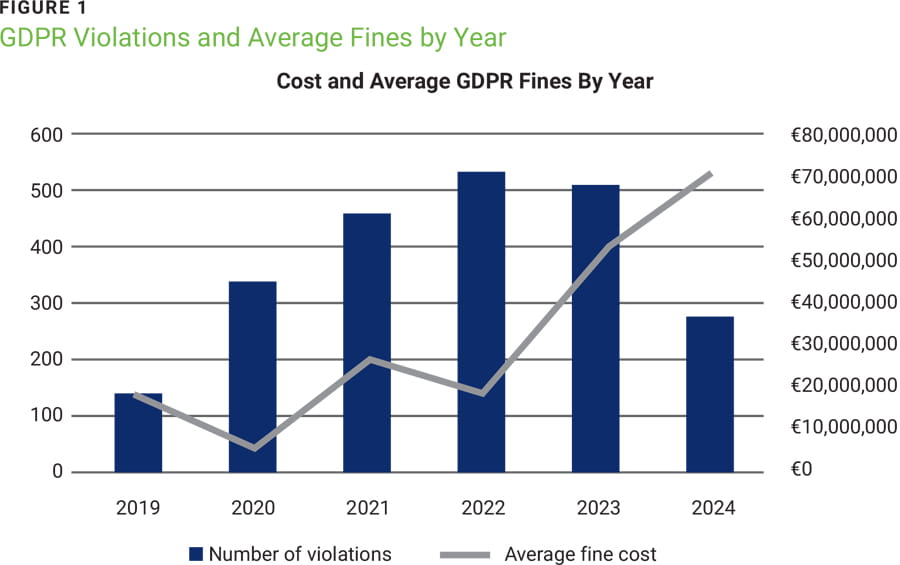

The number of violations and cost of penalties incurred due to GDPR noncompliance were collected from the start of enforcement (May 2018) through April 2025 using the CMS.Law GDPR Enforcement Tracker.7 Figure 1 demonstrates that in 2019, there were 143 violations, and this number peaked in 2022 with 536 violations. Since this peak, there has been a steady decline in the number of violations reported each year, but the average cost of each fine continues to increase.

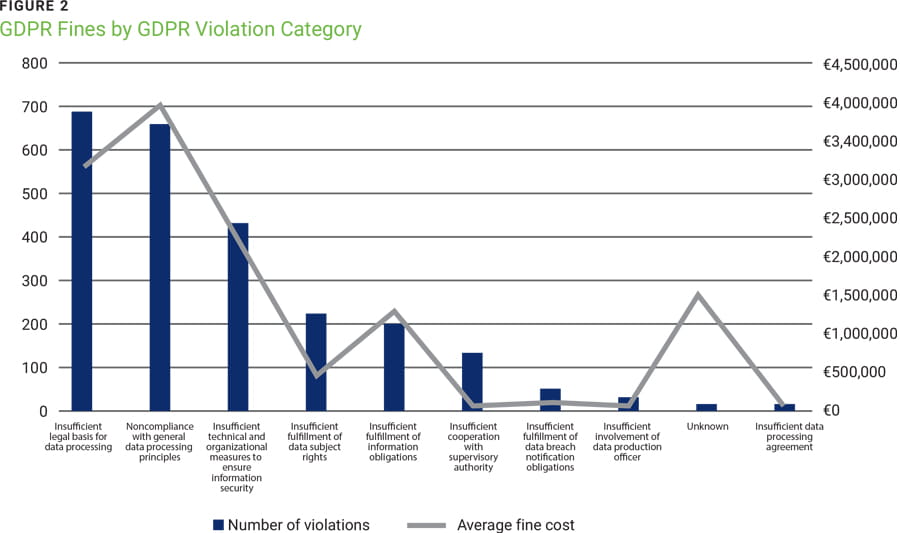

The 2022 increase in the number of fines may have been due to the lag in developing infrastructure with the ability to investigate and enforce the GDPR. The subsequent decline may be the result of increased compliance with the regulation. Evidently, the European Union effectively established privacy norms, created a mechanism for investigating data privacy violations, and demonstrated a willingness to assess penalties for noncompliance. Figure 2 provides more context, atomizing the data by separating the violations by GDPR category.

The most common violation identified by the GDPR is “insufficient legal basis for data processing:” 676 violations have occurred since enforcement began. The concept of having a legal basis for data processing is in Article 6 of the GDPR, which details the instances in which it is legal to process personal data. Moreover, the highest average fine (€3.8 million) is associated with “noncompliance with general data processing principles,” which was the second most common violation, with 643 total violations.

What is clear is that enterprises are being held accountable for their use, misuse, or mismanagement of personal data.The bottom line is that organizations should not collect, store, or sell personal data unless the organization can justify the process. In essence, organizations are accountable for how they use private information. According to GDPR Article 5.1-2, the seven GDPR protection and accountability principles organizations should follow are:

- Lawfulness, fairness, and transparency

- Purpose limitation

- Data minimization

- Accuracy

- Storage limitation

- Integrity and confidentiality

- Accountability

The final principle, accountability, may be the most important. It states that “The data controller is responsible for being able to demonstrate GDPR compliance with all of these principles.”8 Based on this information, it can be inferred that the most common GDPR violations, and the ones resulting in the highest fines, are associated with organizational accountability for data collection and protection.

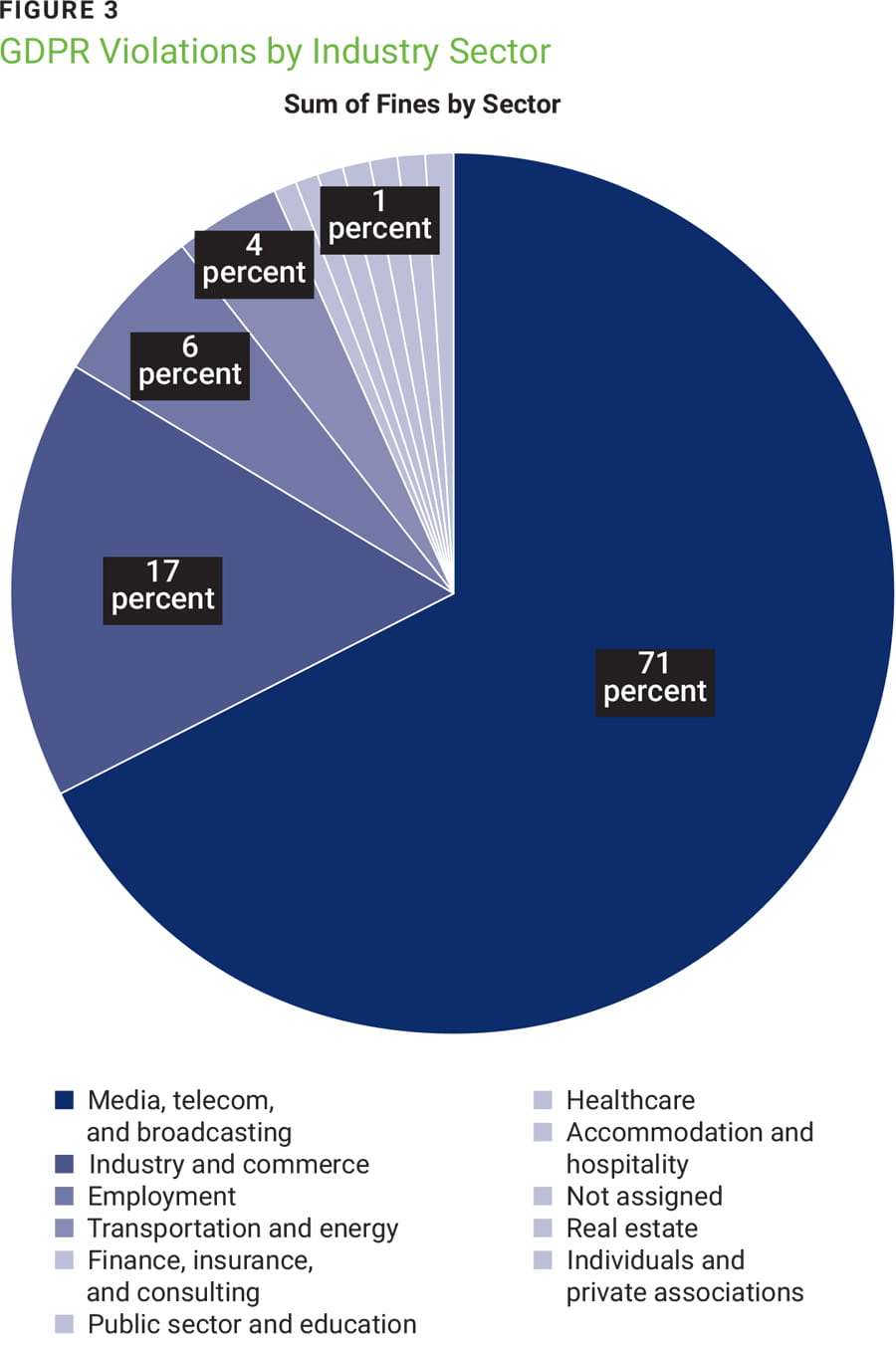

Compliance with data collection and usage norms begins with the creation of a data security accountability culture at the organizational level.The final area of inquiry is an analysis of GDPR fines based on industry sector. Figure 3 shows that the media, telecom, and broadcasting industries have incurred 71% of all violations since enforcement began in 2019. This could be attributed to the large amount of customer data these industries handle and process. The second-highest category, industry and commerce, demonstrates that GDPR enforcement applies across sectors and that all organizations should be concerning themselves with data privacy principles and accountability.

The increasing number of GDPR violations demonstrates the European Union’s commitment to enforcing individual data privacy rights across all industry sectors. The GDPR has also proven to be the bellwether for other legislative and regulatory bodies. For example, in the short time since the GDPR was enacted, the European Union has issued the NIS2 Directive, which imposes minimum cybersecurity standards; the Cyber Resilience Act, which addresses further mandatory cybersecurity requirements; the Revised Standard Contractual Clauses (SCC), which address the transfer of personal data; and the Artificial Intelligence (AI) Act, which includes regulations for the processing of personal data with AI.9 Similarly, other countries have enacted legislation such as the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) of the People’s Republic of China, India’s Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, Thailand’s Personal Data Protection (PDPA) Act, and the United Kingdom GDPR (UK-GDPR), to name a few.10

Cost of Compliance vs. Penalties

The growing number of GDPR violations and legislation coincide with the fact that 74% of organizations find regulatory complexity to be a major challenge in achieving data privacy and protection compliance.11 This complexity is compounded by the fact that data protection compliance can cost organizations between US$7.7 million and US$30.9 million annually, depending on the industry sector.12 This creates a conundrum for organizational data managers: Is the cost of compliance higher than the cost of incurring penalties from multiple regulatory bodies due to noncompliance? This question is especially pertinent as it becomes increasingly difficult to keep track of all regulations and requirements.

Contending with this question begins with a conceptual approach to data privacy compliance, one that addresses the accountability associated with having access to personal data.

Accountability as a Social Construct

Accountability is defined as the “relationship between an actor and a forum, in which the actor has an obligation to explain and to justify his or her conduct, the forum can pose questions and pass judgment, and the actor may face consequences.”13

A conceptual approach to accountability involves viewing accountability as a framework or principle. This includes defining what it means, why it matters, and how it should guide behavior. Taking a conceptual approach to accountability enables organizations to understand the “why” of protecting personal data, allowing them to focus on how they collect, process, and use that data. This empowers organizations to meet the intent of current and future laws and regulations without necessarily needing to focus on the nuances of each one.

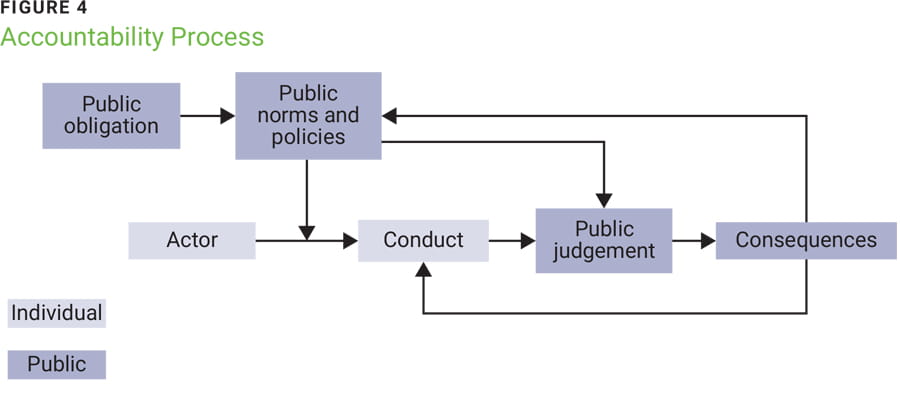

From a data privacy perspective, accountability begins with the forum (the general public) identifying behavioral norms by which it can judge the actor’s (organizations handling public data) conduct, pass judgment, and assign consequences based on those actions. Figure 4 further outlines this process, where the individual actor is represented in dark blue and the public is shown in light blue.

Actors (organizations) must recognize that their data privacy conduct does not take place in a vacuum. Actors rely on the forum (public) to create public norms and policies associated with the use of private data. It is also the responsibility of the forum to pass judgment on how the actor’s conduct complies with these social norms and policies. Finally, the forum must administer consequences to both change the actor’s conduct and reinforce the public norms and policies. On the surface, this seems simple. However, there are several issues that cause agents to stray from accountability.

One major problem with accountability is that many leaders struggle with enforcing it.14 A Partners in Leadership study found that 82% of managers admit they struggle to hold employees accountable.15 Returning to the conceptual approach to accountability, the organization now takes on the roles of both agent and forum. As the forum, the organization must define norms and policies, judge employee actions, and administer consequences to ensure that it can be a better agent to the public. However, the study also found that 85% of employees are unclear about organizational goals.16 The relationship between managerial ineffectiveness and disorganized employee culture comes back to a lack of accountability. Accountability is absent from the majority of organizations because there is an absence of norms, judgments, and consequences that guide and correct employee actions and reinforce the organization’s policies. Thus, compliance with data collection and usage norms begins with the creation of a data security accountability culture at the organizational level.

Create a Culture of Data Security, Collection, and Usage Accountability

Creating a culture that values data privacy starts with developing the tools the organization will use to ensure that it is accountable for managing internal and external private customer data. There are 10 steps that organizations can implement to foster this kind of culture.

Step 1: Evaluate the Current Organizational Level of Accountability

Assessing employee attitudes towards accountability is often conducted through surveys that focus on five dimensions of accountability.17 Figure 5 addresses each of these components and gives sample survey statements that organizations can use to assess employee accountability attitudes toward the protection of public data.

Figure 5—Accountability Dimensions and Potential Survey Statements

| Dimension | Description | Sample Survey Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Attributability | Individuals expect their contributions, errors, or activities to be linked to them. | What I do with public data is noticed by others in my organization |

| Observability | Individuals expect their job-related activities to be seen by others. | Anyone outside my organization can tell whether I am handling public data responsibly |

| Evaluability | Individuals expect that their activities will be reviewed based on specified criteria. | The outcomes of my work that is associated with public data are rigorously evaluated |

| Answerability | Individuals expect to give reasons for their actions. | I am required to follow strict organizational policies about the use and storage of public data |

| Consequentiality | Individuals expect their actions to be rewarded or sanctioned. | If I misuse public data my organization will be punished |

The survey questions are derived from a five-dimensional employee accountability scale developed by Yonsueng Han and James Perry.18 The five dimensions closely follow the accountability construct where actors are aware of public norms, and aware that their actions will be judged and consequences will follow. Such a survey reminds employees that handling public data comes with both privilege and responsibility at the individual and organizational level, and accountability comes with the implicit and explicit expectation that one may be called on to justify their beliefs, actions, and feelings.19 Similarly, the survey results provide managers with an understanding of where their organizations have strong accountability and where it could be improved.

Designing and implementing an accountability survey helps address the public’s concern regarding organizational accountability for the way data is processed.

Step 2: Establish a Data Organization Chart for Accountability

Research has shown that individuals are more critical in their thinking and actions when they believe they will be accountable to an audience.20 Creating an organizational chart that lists employees and their data security roles helps foster a culture of accountability. This is because when employees understand clearly the roles and responsibilities of their peers, they can more easily hold one another accountable and maintain data integrity.

Step 3: Understand Current Data Security and Data Usage Procedures

The organizational leader responsible for data security and usage must be aware of the requirements for storing, using, and transferring personal data. This duty cannot be transferred to another person. Others in the organization may also be aware of these requirements, but overall accountability for the organization must reside in one person.21

Step 4: Set Internal Data Privacy Policies and Procedures

The conceptual understanding of accountability states that actors consider social norms and consequences before they act. Organizations must therefore set these norms for their organizations. Many of these policies are likely already in place. At a minimum, a policy must include stipulations for data storage, usage, and transfer that address the national and international standards under which the organization operates. These policies should be compiled and managed by one central agent inside the organization. This includes updating the policies to meet changing national and international requirements.

Step 5: Educate Organization Members on Policies

Employees want to know what is expected of them. Therefore, employee training should be seen as a means of keeping organization members informed of the ever-changing world of data management and the public expectations of how their data is used. Training should be scheduled and mandatory, so every actor (employee) understands the potential consequences incurred if policies are not followed.

Step 6: Encourage Employees to Hold Each Other Accountable

Creating a culture of accountability includes encouraging employees to hold each other accountable. Again, this requires individuals to act as both the agent and the forum. The employee is the agent when handling public data. Conversely, the employee is the forum when observing the actions of other employees (agents) around them. This concept has become increasingly difficult for many organizations since employees are not always comfortable enforcing organizational norms. Instead, employees remain quiet, which leads to team dysfunction.22 Encouraging employees to give constructive feedback to their peers, such as “That does not seem to comply with our data privacy culture,” alters the accountability concern from a person-to-person conflict to a person-organization conflict.

Step 7: Publicize Deficiencies Internally and Externally

The nature of accountability assumes that there will be failures.23 Admitting to shortcomings at the individual and organizational level demonstrates to consumers that while the organization may be trying to manage difficult processes or issues that lead to failures, it is also making improvements based on these inevitable failures. This reporting should be done as quickly and with as much transparency as possible.

Step 8: Evaluate Emerging Technology’s Influence on Policies and Procedures

One issue associated with many emerging technologies is the lack of understanding regarding how data is being used and impacting decisions. These technologies (e.g., AI, machine learning [ML]) often have embedded black boxes producing information or recommendations that are not intuitively understood by the user.24 Organizations must therefore understand how personal data is being used by each of these emerging technologies and educate organizational members on the potential issues associated with trusting the technologies that are black boxes when it comes to personal data.

Step 9: Extend Data Accountability Culture to External Partners

Personal data is often shared with many external partners, and these partners must understand the importance of data accountability to the organization. Returning to the concept of accountability, the organization must define the rules regarding the way personal data is used by its partners. This begins

with discussing data security and usage expectations with enterprise partners and explaining that their actions will be evaluated and consequences will be administered.

Step 10: Continue to Improve Data Accountability

Organizations should schedule annual evaluations to review accountability surveys, processes, and emerging technology threats, and identify areas for improvement. Include these results in employee training and demonstrate the commitment the organization has to being accountable for the use of public information.

Conclusion

It is impossible for organizations to thwart every effort by data criminals and to fend off potential internal misuses of personal data. However, organizations should not defer to the approach that it is cheaper to pay penalties if caught than to plan for every potential misuse and abuse of personal data. Each organization is therefore accountable to the public to protect, use, and transfer personal data in a manner that is acceptable to the public. Understanding the burden associated with this level of trust can then be managed by creating a culture of data privacy accountability where organizations can explicitly state to their customers how and why data was used. By engaging with consumer data in a way that prioritizes accountability, organizations can ensure that trust is maintained and private data is secure.Endnotes

1 Ludington, S.; “Reigning in the Data Traders: A Tort for the Misuse of Personal Information,” Maryland Law Review, vol. 66, iss. 1, 2006, p. 140-193

2 Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation [GDPR])

3 Hickman, T.; Gabel, D.; “Data Protection Laws and Regulations: The Rapid Evolution of Data Protection Laws 2024-2025,” ICLG—Data Protection Laws and Regulations, 31 July 2024

4 Wolford, B.; “What Is GDPR, the EU’s New Data Protection Law?,” GDPR.EU

5 Wolford; “What Is GDPR”

6 Wolford; “What Is GDPR”

7 CMS.Law, “GDPR Enforcement Tracker,”

8 CMS.Law, “GDPR Enforcement Tracker”

9 European Commission, "Directive on Security of Network and Information Systems (NIS 2 Directive)," European Union; Regulation (EU) 2024/2847 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2024 on horizontal cybersecurity requirements for products with digital elements and amending Regulations (EU) No 168/2013 and (EU) 2019/1020 and Directive (EU) 2020/1828 (Cyber Resilience Act); European Commission, “Standard Contractual Clauses (SCC)”; EU Artificial Intelligence Act, “High-Level Summary of the AI Act,” 27 February 2024

10 Personal Information Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, 2021; The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, India, 2023; Personal Data Protection Act, B.E. 2562, Thailand, 2019; “Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council,” United Kingdom

11 ISACA®, Protiviti, IT Audit Perspectives on Today’s Top Technology Risks, 2022

12 Globalscape, “Non-Compliance 2X the Cost of Compliance. Can You Afford the Risk?”

13 Bovens, M.; “Analysing and Assessing Accountability: A Conceptual Framework,” European Law Journal, vol. 13, iss. 4, 2007, p. 447-468

14 Little, J.; “The Cost of Avoiding Accountability: Leadership Mistakes That Hurt Business Growth,” LinkedIn, 2 April 2025

15 Little; “The Cost of Avoiding”

16 Little; “The Cost of Avoiding”

17 Han, Y.; Perry, J.L.; “Employee Accountability: Development of a Multidimensional Scale,” International Public Management Journal, vol. 23, iss. 2, 2018, p. 224-251

18 Han; Perry; “Employee Accountability”

19 Lerner, J.S.; Tetlock, P.E.; “Accounting for the Effects of Accountability,” Psychological Bulletin, vol. 125, iss. 2, 1999, p. 255-275

20 Lerner; Tetlock; “Accounting for the Effects”

21 Wood, J.A.; Winston, B.; “Toward a New Understanding of Leader Accountability: Defining a Critical Construct,” Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, vol. 11, iss. 3, 2005, p. 84-94

22 Lencioni, P.; The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, Jossey-Bass, USA, 2002

23 Wood; Winston; “Toward a New Understanding”

24 Aich, S.; Burch, G.; “Looking Inside the Magical Black Box: A Systems Theory Guide to Managing AI,” ISACA® Journal, vol. 1, 2023

GERALD F. BURCH | PH.D.

Is an assistant professor at the University of West Florida (Pensacola, Florida, USA). He teaches courses in information systems, operations management, and business analytics at both the graduate and undergraduate levels. His research has been published in twelve ISACA® Journal articles over the past three years, and he has extensive research published in several other top peer-reviewed journals. Burch has helped more than 100 organizations with his strategic management consulting and can be reached at gburch@uwf.edu.

JANA BURCH | ED.D.

Is a faculty member at the University of West Florida, where she teaches undergraduate business courses in communication, ethics, management, and entrepreneurship. In addition to her teaching responsibilities, Burch works with organizations to provide business development support and create innovative business solutions. Her research interests include workforce development, innovation, creativity, and entrepreneurship. Burch is dedicated to helping her students and clients develop the skills and knowledge necessary to succeed in the business world.