Every cybersecurity risk ties back to an asset. Insider threats, ransomware, supply chain attacks, and even regulatory noncompliance all involve a physical, virtual, or human asset. Depending on the organization, assets can include endpoints, containers, cloud infrastructure, shadow IT, unmanaged devices, and industrial control systems (ICSs). The persistent evolution of cyberthreats, characterized by sophisticated tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) alongside threat actors targeting organizational assets, requires organizations to adopt a proactive and intelligence-led security posture. Central to this posture is asset visibility: the comprehensive, dynamic documentation of all digital and physical infrastructure in an enterprise.

In other words, asset visibility is knowing the who, what, where, when, and how of all information and operational technology in an enterprise, for the purposes of scalable threat detection, analyses, response, and compliance. As environments become more complex, full asset visibility is essential. Without it, even the best security tools and teams lack the context needed to detect threats, prioritize risk, and respond effectively to security alerts.

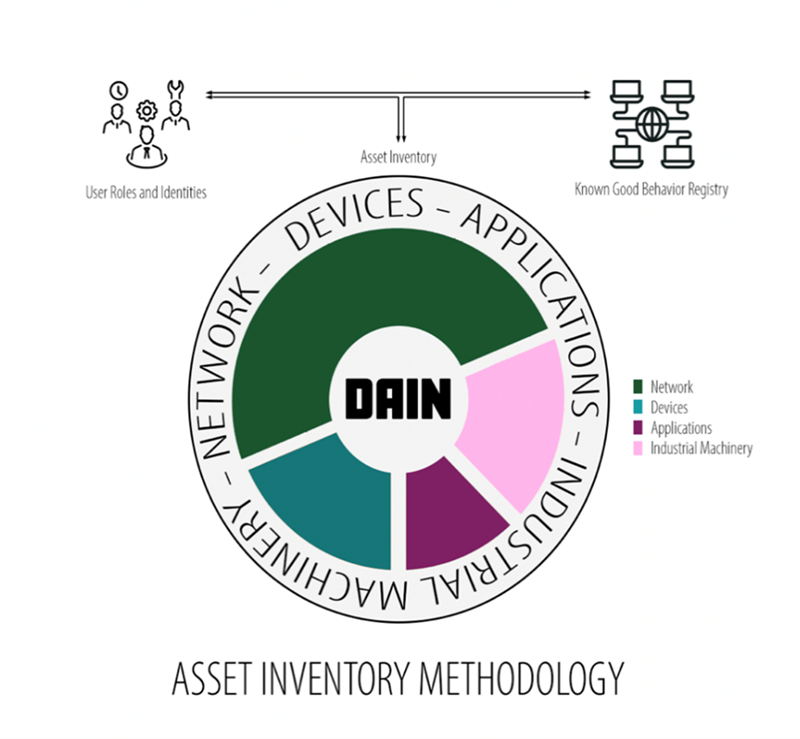

Achieving comprehensive asset visibility requires a structured yet modular framework that can adapt to the growing complexity of modern enterprise environments. The DAIN methodology provides such a framework by organizing and aligning asset visibility efforts across 4 critical domains: Devices, Applications, Industrial Machinery, and Networks. This structure helps organizations approach asset visibility in a consistent and methodical way, ensuring no major asset is unaccounted for. As a result, the DAIN methodology enables accurate and real-time asset visibility in an enterprise, strengthening both security posture and operational efficiency.

The Risk of Visibility Gaps

Asset visibility has moved far beyond simple inventory exercises and is now a fundamental strategy that determines how organizations detect, investigate, contain, and recover from attacks when they occur. This shift reflects the reality that an organization cannot protect what it cannot see. Without a clear understanding of what assets exist, where they are located, and the state they are in, organizations are unable to effectively detect intrusions, hunt for indicators of compromise (IoCs), or contain threats before they escalate. Thus, the lack of a detailed, accurate, accessible, and regularly updated asset inventory introduces coverage gaps for assets, increasing the likelihood and impact of a cyberattack.

Unmanaged or unknown devices within organizations present a significant security and business risk, as attackers often exploit these devices to launch ransomware and/or steal data without detection. Microsoft’s Digital Defense Report 2024 supports this claim, revealing that more than 90% of ransomware incidents involved the exploitation of unmanaged devices.1 Ransomware recovery costs average , according to Sophos, and visibility gaps significantly contribute to this expense.2 Further, during incident response, asset coverage gaps force security teams to rely on guesswork, wasting valuable time and delaying containment efforts. This inadvertently increases the dwell time of attackers in a compromised environment. According to Google’s M-Trends 2024, adversaries remain undetected for an average of 10 days, giving them enough time to escalate privileges, move across systems, and exfiltrate data.3 The longer visibility gaps persist, the greater the risk of undetected breaches and organizational disruption.

Besides the mentioned risk, visibility gaps pose significant compliance and governance challenges. Without a complete asset inventory, organizations may fail to identify systems storing sensitive or regulated data, increasing the risk of noncompliance and costly penalties when audited. These blind spots also hinder the detection of insider threats and the enforcement of security policies, allowing malicious activities to go unnoticed.

Complexities With Asset Visibility

Organizations today face increasing complexity when it comes to managing and securing the scale, diversity, and distribution of enterprise assets. Factors such as digital transformation, remote work, cloud adoption, bring your own device (BYOD) policies, Internet of Things (IoT) device proliferation, and the convergence of operational and information technologies have created a complex and dynamic environment. These challenges are amplified by the speed at which devices can be provisioned and deprovisioned, without triggering alerts, especially in environments that lack automated discovery or real-time tracking. As a result, asset visibility has become a moving target. In this context, achieving 100% asset visibility has become an arduous task for many enterprises. A 2021 study conducted by the Enterprise Strategy Group observed that approximately 79% of organizations reported widening asset visibility gaps.4 Asset visibility challenges directly impact an organization's ability to defend itself, thus necessitating prioritization by the responsible stakeholders within concerned enterprises.

Establishing Asset Visibility With the DAIN Methodology

Actualizing sustainable asset visibility requires an approach that captures both horizontal breadth and vertical depth across the enterprise. Horizontal breadth ensures that all asset types, such as devices, applications, cloud services, and operational technology, are inventoried. Vertical depth maps ownership, access, dependencies, and interconnections between assets. This is where methodologies such as Devices, Applications, Industrial Machinery, and Networks (DAIN) thrive. The DAIN methodology provides a structured way to account for assets comprehensively, ensuring that no layer of the environment is overlooked. A breakdown of the methodology can be seen in figure 1.

Figure 1—DAIN Asset Inventory Methodology5

Devices

The first component of DAIN is the identification of all systems that function as devices within the environment. This includes desktops, laptops, mobile phones, servers, network equipment, and IoT devices. Any hardware-based asset that connects to the enterprise network and runs an operating system should be included. After identifying these devices, it is essential to document what software, operating systems, and services are running on them, as this provides the foundation for accurate inventorying, monitoring, and risk evaluation.

A common challenge with inventorying devices in an enterprise is the implementation of bring your own device and company-owned, personally enabled (COPE) policies in hybrid work settings. While BYOD and COPE offer varied flexibility for both employers and employees in terms of the responsibility of device acquisition and maintenance, these policies introduce complexities in managing security, compliance, and device health. The varied ownership of these devices often leads to inconsistent enforcement of software and security patch updates, making it difficult to accurately assess device health when connecting to an enterprise’s network.

To mitigate this, enterprises can leverage mobile device management (MDM) solutions and implement a centralized, automated update schedule for known devices. This strategy improves the likelihood that devices connecting to the network are up to date with applicable security updates. Employee training also plays a key role in actualizing satisfactory device health as training modules can include specific guidance on an enterprise’s acceptable use policy (AUP). Additionally, unknown IoT devices are also difficult to account for in an enterprise’s asset inventory. As such, asset discovery solutions linked to an asset inventory can identify, remember, and track ghost devices, and provide telemetry to security information and event management (SIEM) systems for behavioral analysis. This ensures that all devices are accounted for and properly monitored.

Applications

Applications, as the second component of DAIN, focuses on identifying and inventorying all software and services running across the enterprise. This includes enterprise applications, operating systems, internally developed tools, software as a service (SaaS) platforms, backend services, and databases. Comprehensive visibility into applications is essential, as outdated, unmonitored, or unauthorized software often introduces vulnerabilities. These gaps can serve as entry points for attackers and increase the organization’s exposure to risk. Vulnerability management tools, including but not limited to Qualys and Tenable.io, can help organizations assess their susceptibility to known common vulnerabilities and exposures (CVEs) and patch accordingly. The US National Vulnerability Database (NVD) documents known vendor software vulnerabilities, risk, and provides patching guidance which commonly link to the vendor advisories for mitigation.6

Additionally, establishing a baseline for application execution and permissions is crucial to detecting anomalies and potential threats. Observing parent–child relationships within processes plays a key role in this effort. Normal application behavior follows predictable patterns of execution, where specific processes spawn known child processes, such as explorer.exe spawning outlook.exe. However, if a browser spawning a command shell is detected, this can indicate malicious activity. Likewise, establishing a baseline for application execution and defining which user roles or business units are permitted to run specific applications or scripts is essential at this step. For example, finance-facing employees should not be executing PowerShell scripts or leveraging remote management tools. As such, automating the discovery and documentation of such relationships and role-specific execution permissions is key to implementing the DAIN methodology.

The longer visibility gaps persist, the greater the risk of undetected breaches and organizational disruption.Industrial Machinery

For enterprises with industrial-facing functions, the third component of DAIN, industrial machinery, focuses on operational technology (OT) assets, which are increasingly integrated with enterprise information systems. OT assets include ICS, Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) platforms, field equipment, IoT, and specialized machinery used in manufacturing or critical infrastructure. These systems often fall outside traditional IT asset management and vulnerability scanning tools, making them challenging to monitor. Notably, many OT systems run on legacy software and proprietary protocols, which may lack basic authentication and encryption features found in other IT assets. As such, accounting for these in the asset inventory would improve asset visibility and be instrumental to microsegmentation efforts, which are recommended for enterprises operating both IT and OT environments. Configuration management and documentation is a key aspect of industrial machinery under the DAIN framework, as unauthorized malicious changes in firmware, control logic, or communication settings can directly impact operational safety and reliability. Considering their increasing connectivity and inherent vulnerabilities, OT systems represent a growing part of the organizational attack surface and thus require dedicated visibility efforts for an improved enterprisewide security posture.

Network

The network component accounts for how devices, applications, and OT systems connect across the enterprise. This includes mapping the network topology, understanding egress and ingress traffic flows, identifying protocols in use, and assessing system-to-system access. Establishing baselines for normal activity, such as traffic volume, communication patterns, and access timing, is key to detecting anomalies when they occur. For example, a human resources (HR) workstation should communicate with the internal HR database server over port 443 (HTTPS) during business hours. However, if the same workstation suddenly generates large volumes of egress traffic to an unfamiliar IP address over an arbitrary port outside of, or even during, business hours, that can be a sign of compromise. Additionally, reviewing segmentation and firewall rules help ensure boundaries are in place to contain threats and limit lateral movement. For example, development environments should always be segmented from production environments.

Why Context Matters in Asset Visibility

A complete asset inventory extends beyond simply cataloging devices and software; it requires enriched context to transform raw data into actionable intelligence. Metadata such as system ownership, business function, physical location, deployment date, traffic flows, maintenance status, access rights, and configuration baselines provide critical insights that add operational value to the inventory. This contextual enrichment enables security teams to prioritize vulnerabilities based on business impact, assign clear responsibility to asset owners, and ensure compliance with regulatory requirements. Furthermore, during active incidents, having detailed context allows responders to make informed, time-sensitive decisions, accelerating containment and remediation efforts. Without this additional layer of information, asset data remains static and difficult to operationalize effectively.

Implementation Approaches for Asset Visibility

The implementation of asset visibility varies depending on factors such as organization size, asset diversity, staff expertise, and existing technology infrastructure. Smaller organizations might prioritize simple endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools, while larger enterprises often require a scalable approach combining multiple methods to achieve comprehensive coverage. The DAIN methodology provides a modular approach to guide these efforts by enabling visibility across several key domains:

- Devices and Applications—Leveraging endpoint protection solutions from vendors not limited to Microsoft or CrowdStrike is a practical starting point. When properly configured, these tools deliver detailed and continuous telemetry on device configurations, installed software, and user activity. Such telemetry supports the mapping of assets to identities and enables monitoring for deviations from known good behavior. Microsoft’s Digital Defense Report 2024 notes that some EDR solutions offer tamper protection, which restricts unauthorized security setting changes, often an early sign of threat activity. In May 2024, Microsoft detected more than 176,000 incidents that involved malicious configuration changes.7 This highlights the importance of documenting configuration settings and outlining change management procedures to ensure that deviations are promptly detected and prevented.

- Industrial machinery—Visibility is more complex as these systems are usually cordoned off. Solutions such as Nozomi Networks or Claroty offer OT-specific asset discovery and passive monitoring, which are critical for capturing data from SCADA systems, programmable logic controllers (PLCs), and IoT-connected machinery.

- Network—Deploying active and passive network discovery tools, such as Qualys, Tenable.io, or open-source options such as NMAP helps to identify devices, services, and traffic flows in use at an enterprise. These tools, when correctly implemented with the right permissions, assist in building a current view of network topology and help detect unauthorized connections or unusual access patterns within an enterprise. This is the stage where flow and user activity baselines are established, and are correctly mapped to assets, user roles, and identities. Insights from this process can then feed directly into firewall rules, segmentation policies, and alerting systems to detect abnormal behavior early. within cloud environments and can be mapped directly to DAIN’s application and network components respectively. Identifying assets that connect to the enterprise network and establishing usage and configuration baselines are necessary for the asset inventorying exercise.

Conclusion

Enterprises are constantly changing, and visibility efforts must evolve accordingly. Comprehensive asset visibility is vital for effective cybersecurity in today’s complex environments. The DAIN methodology supports this effort by helping organizations manage devices, applications, industrial systems, and networks. Context-rich asset data enables better risk prioritization, clearer accountability, and faster incident response. Achieving visibility requires a combination of discovery tools, endpoint monitoring, and solutions tailored to cloud and industrial environments. Closing visibility gaps reduces risk and strengthens resilience, making asset visibility a key investment for business continuity.

Endnotes

1 Microsoft; “Microsoft Digital Defense Report 2024: The foundations and new frontiers of cybersecurity,” Microsoft, 20 December 2024

2 Sophos, The State of Ransomware 2025, June 2025

3 Kutscher, J.; “M-Trends 2024: Our View from the Frontlines,” Google Cloud, 23 April 2024,

4 Axonius; “Study Shows 79% of Organizations Acknowledge an Asset Visibility Gap, Leading to 3X More Incidents,” Axonius, 27 April 2021

5 The Devices, Applications, Industrial Machinery, and Network (DAIN) methodology is a framework created by the author to help guide comprehensive asset inventory and monitoring within enterprise environments. The figure depicts how the DAIN methodology initially incorporates user roles and identities to provide essential context for asset management. With this context, the DAIN methodology is established to document all enterprise assets based on the four categories: devices, applications, industrial machinery, and network. Telemetry collected from the assets including access times, usage patterns, and communication flows are analyzed and validated against a known good behavior registry (KGBR) to confirm expected behavior and detect anomalies. In this figure, Network is represented as the largest segment to reflect its overarching role across other asset types, as both a visibility layer and a control plane. Poorly managed or unsegmented networks can widen the blast radius during active incidents, thus representing a wider attack surface.

6 National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), “National Vulnerability Database,” USA

7 Microsoft; “Microsoft Digital Defense Report”

Gerard Chukwu, GCTI

Is a cyberthreat intelligence specialist with experience in enterprise incident response and threat hunting. He has worked across multiple cybersecurity domains, focusing on analyzing threat actor behaviors, developing intelligence reports, and supporting proactive defense strategies for large organizations. His background includes training in advanced threat detection and response techniques, enabling him to identify and mitigate complex security threats. He is dedicated to translating technical findings into actionable insights that strengthen enterprise security posture.