While augmented reality (AR) has seen increasing use across multiple industries including education and medicine, many users leverage this technology in their daily use of smart phone mobile applications.1 As many individuals either access social media and other websites on their personal smartphones at work or use an office network to visit these platforms, a risk of falling victim to social engineering arises in the workplace digital environment when immersed users become distracted by an AR interface, such as with Instagram or Pokémon GO.2

When a user focuses on both the objects superimposed by the application and the real-world view in the background, additional objects entering their onscreen line of view might not be given sufficient analysis before the user automatically clicks to close out the new object. For instance, if a push notification appears as a tertiary feature within a given AR interface, the user might seek to simply make the new object disappear rather than take time to verify its authenticity or security.

While various studies have emphasized the dangers of social engineering via email and text message,3 less research exists concerning malicious push notifications that manifest on a mobile phone to persuade the user into clicking.4 Furthermore, there has been even less investigation into how attention to the legitimacy of these notifications may be impacted by a user’s level of distraction. This potential oversight could risk users engaging with notifications designed for social engineering or espionage.5

Given the inherent risk of mobile device security in a remote work environment where a user might access a malicious webpage that could install push notifications to perform further social engineering,6 research into user behavior regarding push notifications during instances of distraction within a layered interface such as AR could prove beneficial. Moreover, as studies of AR security have primarily explored privacy concerns rather than social engineering and other threats, the combined risk factors of push notifications within an AR setting warrant deeper investigation,7 particularly with regard to the workplace.

Push Notifications as a Threat Mechanism

Given that attackers often exploit push notifications and pop-up alerts—such as scareware to intimidate a target into clicking a malicious link or executable,8 the use of visceral triggers that evoke a sense of urgency could pose a much more significant threat to a user already distracted by AR immersion in a mobile application such as Google Maps or Pokémon GO.9 This tactic has appeared in incidents such as when threat actors used pop-ups in the Minneapolis Star Tribune to direct users to a website featuring scareware offering to fix a virus on the user’s device for US$50.10 Clicking these types of pop-ups either inadvertently while distracted or due to legitimate anxiety over device infection could result in actual compromise of a user’s device.

As attackers continue to employ push notifications and other pop-ups delivered via malicious drive-by downloads on compromised websites, some users may choose to ignore device update notifications out of either indifference or suspicion.In a professional setting, pressures for social interaction arise similar to those appearing in a social setting,11 including while using a mobile device. Many social applications involve both an AR component and use push notifications.12 In light of the potential for users to compulsively engage with push notifications due to a fear of missing out, attackers could capitalize on this behavior by crafting notifications with a sense of social obligation and time sensitivity.13

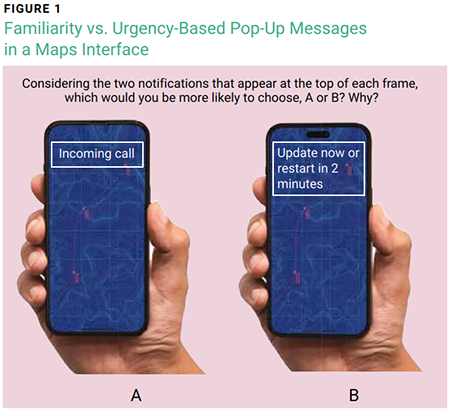

In light of the complex interaction among the narrow user interface (UI) of a mobile phone, the enhancements provided by an AR application, and the appearance of a pop-up, this study investigates the impact of user attention capacity on response to push notifications. Adopting the common social engineering themes of familiarity and urgency often seen in malicious pop-up messages, this research examines whether users tend to respond more frequently to an onscreen notification about an incoming call (familiarity) versus an update notice (urgency).

In a similar study prioritizing personal compared to workplace use of AR smartphone applications, the majority of participants elected to click on a pop-up notification about an incoming call as opposed to an update-or-restart warning. This preference stemmed from both reluctance to miss a connection and suspicion over update notices.14 The researchers hypothesize that a similar communicative compulsion will lead the majority of participants to prioritize incoming calls in this study as well.

While a malicious push notification can theoretically contain any type of message, given that many work devices will eventually update automatically, the researchers anticipate that most participants will click on the incoming call notification to avoid potentially missing a call from a manager or coworker. However, in a workplace context, a device restart warning gains additional significance. Users who rely on their devices for work tasks will seek to prevent sudden shutdowns during critical work moments.

Methodology

To further explore how users react to the appearance of push notifications during AR immersion on a smartphone interface, this research used a qualitative phenomenological methodology involving 50 participants’ in-depth behaviors when faced with onscreen notifications while using four different AR mobile applications. Subjects were recruited from a pool of individuals aged 18-40 who attested to using the smartphone-based AR applications Google Maps, Pokémon GO, and Instagram while at the physical workplace or while working remotely on an employer network. There were no significant differences in gender or race among participants.

Materials

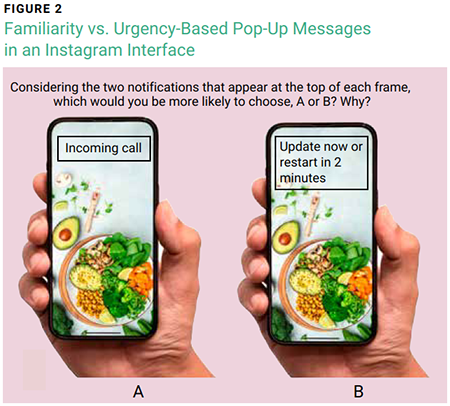

To test the hypothesis, this study used a visual presentation including animation-enhanced AR application interfaces to simulate immersion, with the addition of push notifications identically positioned for both options on each interface. This presentation contained interfaces for Google Maps, Pokémon GO, and Instagram. Participants were asked whether, in a workplace context, they would choose option A (incoming call―familiarity theme) or option B (update notice―urgency theme) from the two simulated push notifications in each of the interfaces, and then to explain the reasoning behind their decisions.

Various AR application interfaces were used to broaden the number of applications with which participants were familiar to better establish the pop-up message text itself as the constant.

Figure 1 illustrates how push notifications can exemplify a social communication-themed lure and an urgency-themed lure, respectively, on a Maps interface.

Figure 2 depicts push notifications displaying a social communication-themed lure and an urgency-themed lure, respectively, on an Instagram interface.

Results

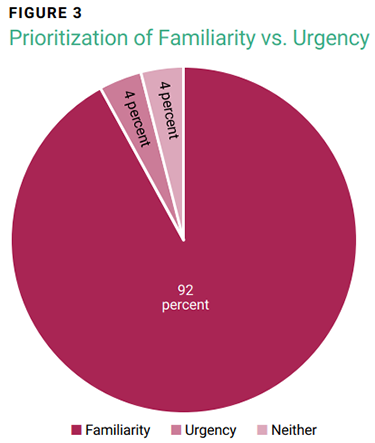

As predicted, a review of participant responses revealed an overall skew toward selection of option A (familiarity theme). A common justification involve assuming that an incoming call during work hours would always need to take precedence over a device update.

Similar to the aforementioned study on distraction during AR immersion in a personal setting, two users also reported never trusting device update notices as a rule. Meanwhile, for most participants, the reluctance to miss a connection either in a social or professional context seemed to typically supersede the importance of a device update, including an update that warned about an impending device restart.

A common theme among responses emphasized an aversion to miss a communication attempt, unless their device warned the call to likely be spam, an intriguing point to consider for future potential mitigation of susceptibility to malicious push notifications in a mobile AR interface.

Of the 50 interviewees, 46 chose A (familiarity), and two chose B (urgency). The reason given by the two respondents who selected option B prioritized the need to prevent a device restart during work hours. Only two respondents reported, unprompted, to not trusting either option due to risk aversion regarding potential social engineering (figure 3).

Of the 50 interviewees, 46 chose A (familiarity), and two chose B (urgency). The reason given by the two respondents who selected option B prioritized the need to prevent a device restart during work hours. Only two respondents reported, unprompted, to not trusting either option due to risk aversion regarding potential social engineering (figure 3).

Discussion

As the majority of participants opted to click on a push notification or pop-up showing an incoming call rather than a notification about an impending forced device restart, the hypothesis holds that the pressure for social interaction tends to take precedence over the threat of a sudden device reboot. Indeed, participants who cited the social obligation described a concern that their manager might be trying to contact them.

As attackers continue to employ push notifications and other pop-ups delivered via malicious drive-by downloads on compromised websites, some users may choose to ignore device update notifications out of either indifference or suspicion. However, when confronted with a pop-up message indicating an incoming call from someone in their recent contacts list, few are likely to ignore it.

Devices that have already fallen victim to malicious deliverables displaying such messages might be vulnerable to push-bombing, a method by which an attacker floods the device with push notifications to tamper with multifactor authentication (MFA) settings in an attempt to access further information about the device and its user. Should a threat actor compose a push notification with a message stating that one of the user’s coworkers is trying to get in touch, the increased likelihood of users to either prioritize such a message or simply click to make it disappear to attend to later, while otherwise engaged with the distractive input of AR, could pave the way for such a compromise.

Limitations and Future Research

This study has various limitations, including a certain degree of ambiguity in the extent to which differences in the visual details of the simulated AR interfaces may have impacted the way participants perceived the text of the displayed pop-up message, despite the messages being identical across the three interfaces. Moreover, as an option to ignore both messages was not included for purposes of avoiding a potentially leading question, more participants might have selected to ignore both, had they the option.

Furthermore, the phenomenological research method focused on the detailed responses of a select group for a closer assessment of the rationale behind participants’ choices. Meanwhile, future research might benefit from studying the same tendencies across a much larger pool, perhaps within a quantitative framework for a wider range of data. Additionally, as products such as Microsoft Teams implement AR features, similar studies focusing on more workplace-specific interfaces can be explored.

Conclusion

Distraction due to the processing of multilayered visual input can result in decreased user awareness when the user is presented with additional information. Push notifications and similar pop-ups that aim to evoke responses of either familiarity or urgency add an extra layer to the already two-tiered mobile phone interface, and any in-use AR applications run the risk of evading a user’s full attention to detail, and thus may lead to the user clicking on a malicious pop-up. Further research into how to better detect such objects moving into the user’s line of sight could support attack mitigation efforts from both a user and developer standpoint within the context of AR on a mobile interface.

From a user awareness standpoint, organizations could consider implementing mandatory social engineering awareness training programs alongside strict policies on the use of personal applications during working hours or using employer-issued devices. Such training could focus on cautioning users against engaging with any unexpected communication invites while connected to the employer network or while using the employer device.

From a developer standpoint, developers with a specific focus on AR applications could prioritize implementation of a security monitoring layer that detects and notifies users regarding any suspicious content in incoming push notifications and other unexpected pop-ups. This hypothetical layer could be designed to vet incoming notifications by identifying the presence of certain keywords in content not native to the device and related to contact invitations, such as a connection calling in. Ideally, all developers contributing to employer issued devices at an organization would be required to integrate such a security layer into these devices.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted under advisement by Dr. Alexander E. Voiskounsky at Capitol Technology University (Laurel, Maryland, USA).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Endnotes

1 Katz, S.; “User Susceptibility to Social Engineering in AR Environments,” ISACA® Journal, vol. 2, 2023, https://www.isaca.org/archives

2 Buchner, J.; Buntins, K.; et al., “The Impact of Augmented Reality on Cognitive Load and Performance: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, vol. 38, iss. 1, 2022, p. 285–303, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12617

3 Moustafa, A.; Bello, A.; et al., “The Role of User Behaviour in Improving Cyber Security Management,” Frontiers in Psychology, 2021, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8253569/

4 Haworth, J.; “MFA Fatigue Attacks: Users Tricked Into Allowing Device Access Due to Overload of Push Notifications,” The Daily Swig, 16 February 2022, https://www.portswigger.net/daily-swig/mfa-fatigue-attacks-users-tricked-into-allowing-device-access-due-to-overload-of-push-notifications

5 Satter, R.; “Governments Spying on Apple, Google Users through Push Notifications–US Senator,” Reuters, 6 December 2023, https://www.reuters.com/technology/cybersecurity/governments-spying-apple-google-users-through-push-notifications-us-senator-2023-12-06/

6 Sabin, J.; “The Future of Security in a Remote-Work Environment,” Network Security, vol. 2021, no. 10, 2021, p. 15–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1353-4858(21)00118-5

7 de Guzman, J. A.; “Security and Privacy Approaches in Mixed Reality: A Literature Survey,” ArXiv.org, 10 June 2020, https://www.arxiv.org/abs/1802.05797

8 Siddiqi, M. A.; “A Study on the Psychology of Social Engineering-Based Cyberattacks and Existing Countermeasures,” Applied Sciences, vol. 12, iss. 12, 2022, p. 6042, https://doi.org/10.3390/app12126042

9 Montañez, R.; Golob, E.; et al.; “Human Cognition Through the Lens of Social Engineering Cyberattacks,” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 11, 2020, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01755/full

10 Komando, K.; “Scareware: One of the Scariest Cybersecurity Attacks in 2022,” 28 August 2023, Kim Komando,

11 Frauenstein, E. D.; Flowerday, S.; “Susceptibility to Phishing on Social Network Sites: A Personality Information Processing Model,” Computers & Security, vol. 94, 2020, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167404820301346?via%3Dihub

12 Ahmad, M. B.; Hussain, A.; et al.; “The Use of Social Media at Work Place and Its Influence on the Productivity of the Employees in the Era of COVID-19,” SN Business & Economics, vol. 2, 2022, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s43546-022-00335-x

13 Gupta, M.; Sharma, A.; “Fear of Missing Out: A Brief Overview of Origin, Theoretical Underpinnings and Relationship with Mental Health,” World Journal of Clinical Cases, vol. 9, iss. 19, 2021, p. 4881–4889, https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i19/4881.htm

14 Op cit Katz

SARAH KATZ

Is a cybersecurity technical writer at Microsoft with seven years of experience in the information security industry, including roles at NASA and Facebook. Her book Digital Earth: Cyber Threats, Privacy and Ethics in an Age of Paranoia was published in early 2022. She has also published articles in Cyber Defense Magazine, Dark Reading, and Infosecurity Magazine.