The world is becoming increasingly digital, both in individuals’ personal lives and in the workplace.1 The digital landscape brings many benefits (e.g., being able to book a vacation from the comfort of your home, tracking packages and the progress of the shipping process without leaving your desk) as well as new challenges (increased complexity, novel security threats, etc.). This co-occurrence of new possibilities and challenges is a common historical trend. A popular example would be the transition from horse-drawn carriages to automobiles as a means of transportation. This transition ushered in a plethora of new opportunities for military operations, while simultaneously introducing challenges for the security of specific geographic regions.

It is safe to say that digital has become the norm. Ross et al., in their book Designed for Digital,2 illustrate the transition from a traditional (analog) business model, via a digitized business model (e.g., replacing paper with PDF), to a fully digital business model that leverages the possibility that new technology offers. This transition from analog to digital makes it increasingly important to effectively protect (the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of) digital assets.

Many organizations are struggling to acquire sufficiently capable security professionals. Despite recent positive developments, there appear to be several root causes that negatively influence this challenge. First, it appears that the security profession is still dominated by a workforce lacking in diversity in terms of age, gender, and race. Second, society at large may have a strong bias towards people who work in a specific field, such as the IT domain, often assuming that only individuals with backgrounds in these areas are suitable for security roles. This narrow perspective can exclude talented professionals from other disciplines. Third, the focus on traditions and certifications is so strict that it hinders professionals from taking the steps necessary to protect the digital assets of our organizations successfully.

The authors strongly believe that people must come first in an increasingly digital world. They hypothesize that a strategy based on diversity and inclusion in the workforce will help address the challenges around building a strong security capability in organizations. The idea is that fostering a more diverse workforce broadens the spectrum of available resources, enabling us to address cybersecurity issues in novel ways. This research explores the hypothesis that diversity in cognitive processing, such as gender-based perspectives and neurodiversity, may yield innovative insights into addressing security challenges. Specifically, the authors investigate how diverse perspectives can enhance cyberprofessionals understanding and mitigation of security issues.

Research Question and Setup

The authors’ research objective is to arrive at recommendations for building effective security practices and teams, through evaluating the proposition that diversity and inclusion contribute to an effective cybersecurity function in organizations. They organized an expert session where scholars and professionals were consulted on this important topic.3

Factors and Definitions of Diversity and Inclusion

Different authors refer to different individual characteristics when discussing diversity. According to Qin et al., the most popular characteristics are race, gender, education, and functional background,4 but others are also used. It is also interesting to note that the way these characteristics are measured differs between authors. Last, many studies use a mono-attribute approach (studying one attribute at a time) rather than a multi-attribute approach (in which the set of attributes as a whole is studied). At its core, diversity is about the variety of different characteristics in a group of individuals which is, in its essence, a neutral and mostly objective notion: once a set of attributes of individuals is selected, one can essentially calculate the degree of diversity in the group. An example of calculating diversity is possible with the Simpson Diversity Index, which considers both the richness (number of different characteristics) and evenness (distribution of individuals among those characteristics) in a group.5

This background provides context on what diversity entails and how diversity can be approached, especially in research. But what is the relationship between diversity and inclusion?

An inclusive workplace is characterized by valuing and leveraging individual and intergroup differences, meeting the needs of underprivileged groups in larger environments, and working with groups and organizations across national and cultural boundaries.6 Therefore, it is important to utilize systems that keep everyone accountable–especially management–for achieving diversity and inclusion goals.

The authors strongly believe that people must come first in an increasingly digital world. They hypothesize that a strategy based on diversity and inclusion in the workforce will help address the challenges around building a strong security capability in organizations.In short, diversity focuses on the demographic breakdown and heterogeneity of groups and/or organizations. Inclusion, on the other hand, focuses on employee belongingness and the integration of diversity into organizational systems.7 Organizational systems that support diversity and inclusion contain practices such as equal access to opportunities, representation at all organizational levels, and leadership commitment to diversity and inclusion.

According to Qin et al., diversity research has mainly focused on six attributes: race, age, gender, education, functional background, and tenure.8 However, there are many other attributes of diversity.9 Attributes can be categorized by dimension (e.g., internal/external/organizational).10

Definitions of Cybersecurity

Cybersecurity is becoming increasingly important as industries head to a more digital future. It encompasses not only the defense of cyberspace but also the defense of those who operate there and any assets that can be accessed through cyberspace.11 Cybersecurity is not only about defending and protecting, it also encompasses risk management, auditing, and compliance.12 Therefore, other terms have been introduced to disambiguate between the two. For example, Schninag, Khapova, and Shahim introduced the term information assurance,13 whereas Bobbert et al., introduced the term digital security assurance.14 The more popular term, cybersecurity, is maintained by the majority of the industry to cover the entire cyberspace realm.

The cybersecurity profession is broad in terms of the required capabilities and expertise. Cyberskill researcher Rafeeq Rehman visualizes the entire scope of cybersecurity and all associated topics every year.15 The model illustrates the main areas that security professionals can focus on. Each area further branches into sub-specialties, highlighting the expansive breadth and depth of the skill set required of the chief information security officer (CISO) and their team. The demand for cybersecurity professionals is growing, and human resource (HR) professionals struggle to acquire the right expertise16 via traditional hiring approaches.

Data Collection and Analysis

The objective of the expert session was twofold: to validate and augment the results of the literature study in light of the research objectives. This ensures results grounded in both literature and the everyday cybersecurity practice. Critical parameters for the session were: (1) the session will be facilitated virtually, (2) the duration of the session must be brief, and (3) both qualitative and quantitative input is desired. The authors used the group support system (GSS) technology, Meetingwizard,17 for data collection.

The quality of an expert session largely depends on the selection of the experts. In this case, the authors sought to bring together a group of experts that met the following criteria: (1) knowledgeable about the field of cybersecurity, (2) demonstrate an interest in research, (3) have experience with managing and/or hiring cybersecurity professionals, (4) are currently employed in the EU region, and (5) represent a balanced mix in terms of gender, age, and level of experience. A total of 19 experts were invited. When sending out the invitations, applicants from the authors’ networks were selected. They did not explicitly request any one gender, age, and experience level, but relied on their knowledge of the target group to compile a mixed group. Ten experts were in the meeting. The expert group achieved a strong balance, comprising 10 participants from diverse backgrounds in HR, cyber and information security management, and risk management. Furthermore, the group included a mix of academics and industry professionals. The expert session included brainstorming and voting steps. The authors did not participate in the brainstorming. However, they participated in the voting process. Study data was collected in a GSS-supported expert panel session on 13 December 2023.

Definitions

Session participants were asked to review the definitions distilled from the literature research phase. Scoring predefined definitions was performed to gauge participants' initial perceptions. It provided valuable insights into the nuanced distinctions the panel experts held between diversity and inclusion. Participants were asked to score the definitions on a 4-point scale (4 = totally agree). These definitions and average scores are

- Diversity (3.3)—Is defined as “the differences in people and the different attributes people have. It is about the differences in perspectives, resulting in potential behavioral differences among cultural groups but also identity differences of group members about other groups."

- Inclusion (3.1)—Is defined as “the degree to which an employee perceives that he or she is an esteemed member of the work group through experiencing treatment that satisfies his or her needs for belongingness and uniqueness.”

- Cybersecurity (3.7)—Is defined as “the approach and actions associated with security risk management processes followed by organizations and states to protect confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data and assets used in cyberspace. The concept includes guidelines, policies, and collections of safeguards, technologies, tools, and training to provide the best protection for the state of the cyber environment and its users.”

Note that the scores are relatively high. Overall, the variance (the degree to which participants disagree with each other) was low for cybersecurity, but moderately high for diversity and inclusion. From the discussion, it was gleaned that the pure distinction between diversity and inclusion caused the variance. It was agreed that diversity can be seen as an objective measure, whereas inclusion is more subjective. However, the main response was that inclusion can be seen from the individual perspective (to what degree does someone feel included in a group) and the group’s perspective (to what degree does the group feel that it includes everyone). This is a very nuanced response. The authors conclude that the definitions are acceptable.

Diversity Factors

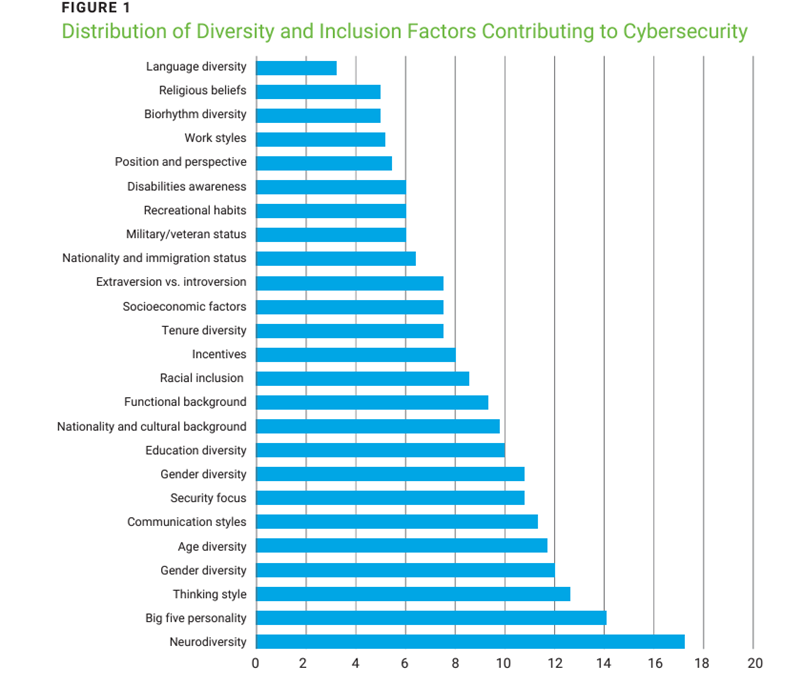

Regarding the diversity factors, the authors presented the participants with their initial list of key factors contributing to diversity/inclusion, notably race, age, gender, education level, functional background, tenure, nationality and cultural background, neurodiversity, and military/veteran status. In total, the participants added 28 new items. The authors observed that there were some (near) duplicates and used GPT4 to cluster the items in a meaningful way. Several factors are highly similar in their meaning. Moreover, some are clearly related (e.g. age and tenure, a very young person most likely does not have as much experience as someone with 20 years of practice). Despite this, the experts agreed that this was the most useful version. Therefore, the authors decided also to use this as the basis for voting. They wanted to determine which factors contribute the most to cybersecurity. To that end, participants were asked to distribute 100 points to these factors. The results are shown in figure 1.18

Perhaps the first item of note is the typical long tail distribution: there is a clear winner, followed by a steep decline, after which the scores diminish gradually. Further, the variability between the different respondents was moderately low. This suggests that respondents are (by and large) in agreement.

The factor for neurodiversity was the clear winner. Respondents commented that this personality trait “contributes to creative problem-solving and innovation in cybersecurity” and that it can generate better “analytical and problem-solving skills which we need [for] cyberissues that can have deep and complex root causes.” Moreover, one of the respondents explained, “I work with [neurodiverse individuals] a lot. [Neurodiversity] has high added value. The group members tend to have a hyperfocus, which helps with complex problem solving. Also, they think differently—just like people who try to break into our systems. The [neruodiverse] group excels at this point.”

After this factor, the scores trail off. At first view, it may seem that there is no rhyme or reason to the scores in the graph. However, a pattern emerges when the results are compared to the aforementioned internal/external dimensions.19 Through this comparison it can be observed that the top five factors (and a large part of the top 10) are internal. The external factors are also shown, but further down the list.

The participants emphasized in their comments: (1) the need for openness and creativity to prevent do-what-the-neighbor-does solutions, (2) the need for situational awareness—theory and thinking have their place, but perhaps not in the middle of a crisis, (3) finding a way to deal with different attitudes towards risk among different age brackets, and (4) that a diverse cultural background can help to understand a wider range of attackers. Perhaps surprisingly, none of the participants explicitly mentioned that a diverse team is more enjoyable to work with, because enjoyment usually correlates with improved team effectiveness.20

These results suggest that a key to building a team that helps improve the security function’s effectiveness is to look for inherent/internal differences among team members. The belief seems to be that we can improve the security function and team effectiveness by building teams diverse in age, gender, and other internal factors. This should be combined with sufficient security focus (ranked 7th) and a mixed functional background (ranked 11th) to create a well-rounded team that can effectively address security challenges.

Impact on HR Processes and Practices

In this phase of the expert session, the focus shifted from attempting to understand the status quo and assessing what factors contribute to effective security teams, to the implications for the HR recruiting and hiring process. Where the former two aim at understanding a desired situation, the latter helps one understand how to obtain desired outcomes.

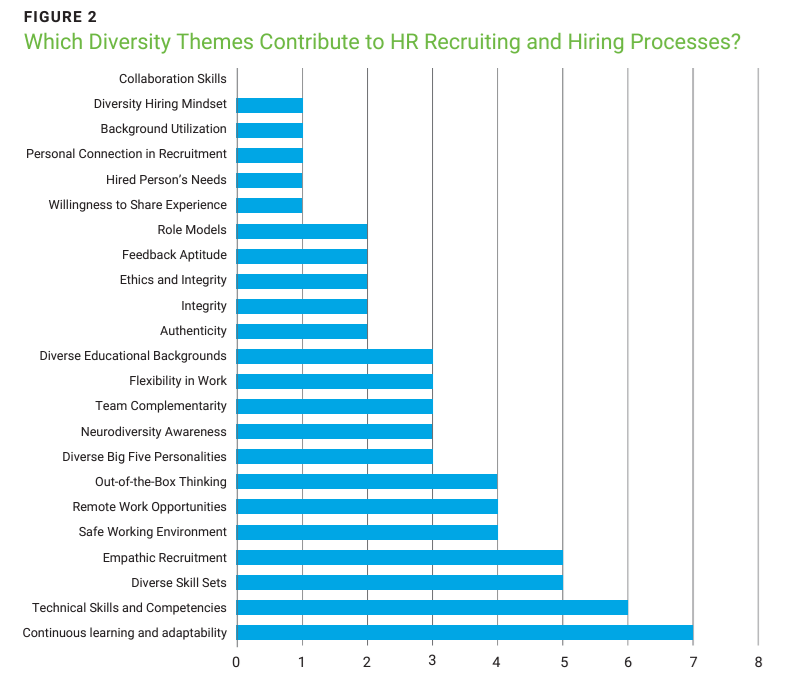

Once more, a brainstorming session was conducted to gather input from the experts. GPT4 was again used for clustering the responses. This activity produced 23 suggestions. Again, the authors noticed that there are factors that could be assigned to the internal, external, and organizational dimensions.21 This time, the group was asked to vote on the importance of these factors by picking five from the list. The results are shown in importance of these factors by picking five from the list. The results are shown in figure 2.

There appears to be a clear top seven in this list, after which the scores slowly trail off. Interestingly, these results contrast with the previous results, which focused primarily on internal personality traits such as age, gender, and mindset. In contrast, the experts’ suggestions for recruiting and hiring are only related to learning and skills (three out of the top seven), which suggests a more traditional mindset. Factors typically associated with diversity and inclusion, such as a safe working environment (5), diverse Big Five personalities (8),22 neurodiversity (9), etc., ranked lower on the list.

In their comments, respondents emphasized that the security field is changing rapidly, requiring up-to-date technical skills and insights. This appears to be a sine qua non: the other factors are also important, but without these skills, other factors become irrelevant. In the context of remote work, it was noted that for neurodiverse individuals, increased focus and fewer interruptions contribute to the effectiveness of neurodiverse team members. It was also stressed that other team members should be aware and empathic towards their neurodiverse colleagues, helping them succeed in contributing to the team as a whole (team complementarity).

Discussion and Conclusion

Cybersecurity is an important discipline in an increasingly digital world, and working towards a diverse and inclusive cybersecurity team will address the shortage in cybersecurity staff and increase the effectiveness of cybersecurity teams.

The concepts of diversity and inclusion are closely related. By and large, people have different characteristics, the diversity of a group is about the degree to which different characteristics are present in a group, and inclusion is about the degree to which individuals feel like/are accepted in the group for who they are. The former is mostly objective: one can essentially quantify how diverse a group is. This measure is neutral because a high or low level of diversity is not claimed to be positive or negative per se. This contrasts heavily with inclusion because inclusion is the degree to which people with different characteristics are accepted (for who they are) by the group in such a way that they can make a useful contribution. The nuance lies in the fact that it is not only about the group members trying to include those who deviate from the proverbial norm; it is also about the effort that the individual makes to become a member of the group. In simple words, it is—or should be—a two-way street.

The experts in the expert panel identified neurodiversity as the most important factor, followed by the Big Five personality characteristics, thinking style, gender, and age. These all fall in the category of internal dimensions (as opposed to external, organizational, or context dimensions).

Based on the qualitative input from the experts, the authors conclude that building a diverse team with a range of ages, genders, and other traits helps to improve the effectiveness of the cybersecurity function. Teams should also have sufficient security focus and a mixed functional background.

This ties in with the recommendations for the HR hiring process in cybersecurity. Here, the experts focus on the condition sine qua non: the need for a security mindset and the ability and willingness to learn. Interestingly, the factors that are typically associated with diversity and inclusion are lower on the list (e.g. safe working environment, diverse Big Five personalities, neurodiversity, etc.) except for (the need for) a diverse skill set.

The authors cannot explain this discrepancy from the data. They suspect that the nature of the work (technical, detailed) inherently puts the focus on (diverse) skills and learning and that this may be a steppingstone to also address the other diversity and inclusion factors. However, the results indicate the importance of a strategic and multifaceted approach to building a cybersecurity team with long-term success. By balancing the required security mindset alongside providing a safe, flexible, and inclusive working environment, cybersecurity teams can foster improved problem solving and innovation.

Cybersecurity teams can benefit from a diverse and inclusive team: diversity will bring a rich set of skills, perspectives, and mindsets to the table. Inclusion will ensure that everyone is valued for their contribution to the effectiveness of the cybersecurity team.

Endnotes

1 Proper, H.; van Gils, B.; et al.; Digital Enterprises Service-Focused, Digitally-Powered, Data-Fueled (The Enterprise Engineering Series), Springer, Switzerland, 2023

2 Ross, J.W.; Beath, C.M.; et al.; Designed for Digital: How to Architect Your Business for Sustained Success (Management on the Cutting Edge), MIT Press, USA, 2021

3 An expert panel study is a research method that gathers insights, opinions, and expertise from a group of individuals considered experts or specialists in a particular field or subject matter. The main objective of expert panel research is to collect, discuss, categorize, and prioritize insights and practices that can guide organizations in understanding how diversity can benefit organizational goals.

4 Op cit Qin

5 Bobbitt, Z.; “Simpson’s Diversity Index: Definition and Examples,” Statology, https://www.statology.org/simpsons-diversity-index/

6 Op cit Booysen

7 Robertson, Q.M.; Disentangling the Meanings of Diversity and Inclusion in Organizations, Group & Organization Management, vol. 31, 2006, p. 212-236

8 Op cit Qin

9 Harvard Human Resources, Glossary of Diversity: Inclusion and Belonging (DIB) Terms, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA; El Bajani, M.; “Leading, and Not Lagging, at the INSEAD Women in Business Conference,” INSEAD, https://intheknow.insead.edu/blog/leading-and-not-lagging-insead-women-business-conference

10 Ibid.

11 Op cit Von Solms

12 Lee, M.; “Stop Looking for the Purple Squirrel: What’s Wrong With Today’s Cybersecurity Hiring Practice,” ISACA® Journal, vol. 2, 2019, https://www.isaca.org/archives

13 Schinagl, S.; Khapova, S.; Shahim, A; “Tensions that Hinder the Implementation of Digital Security Governance,” ICT Systems Security and Privacy Protection, Springer International Publishing, 2021, p. 430-445

14 Bobbert, Y.; Chtepen, M.; et al.; Strategic Approaches to Digital Platform Security Assurance, Information Science Reference, USA, 2021

15 Rehman, R.; “CISO MindMap 2024: What Do Security Professionals Really Do?,” https://rafeeqrehman.com/2024/03/31/ciso-mindmap-2024-what-do-infosec-professionals-really-do/

16 Op cit Lee

17 Meetingwizard, https://www.meetingwizard.nl/en

18 The full list of factors and their explanation is available on request.

19 Op cit El Bajani

20 Patel, B.; Desai, T.; “Effect of Workplace Fun on Employee Morale and Performance,” International Journal of Scientific Research, vol. 2, iss. 5, 2013, p. 323-326, https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Effect-of-Workplace-Fun-on-Employee-Morale-and-Patel-Desai/64ae4dd9488121d256f2df5ad1e2117ebfa425f121 Op cit El Bajani

22 Cherry, K; “What Are the Big 5 Personality Traits?,” Verywell Mind, https://www.verywellmind.com/the-big-five-personality-dimensions-2795422

YURI BOBBERT | PH.D., CISA, CISM

Is chief executive officer (CEO) of Anove International and a professor at Antwerp Management School (Belgium).

MORGAN DJOTAROENO

Is a consultant at Dux Group, a consultancy firm specializing in data, cybersecurity, and process and information management. While Djotaroeno’s professional experience as a consultant is relatively recent, she is an avid learner and has engaged in research projects related to diversity and inclusion and information security behavior.

BAS VAN GILS | PH.D

Is the managing partner of Strategy Alliance and a professor at Antwerp Management School (Belgium).