One does not need to be an expert in information security, business, or networks to recognize that the world is becoming ever more interlinked and connected, reminiscent of a spider’s web. Organizations work with a range of partners, contractors, and suppliers who supply them with hardware, software, and every outsourced service under the sun. This makes supply chain risk management increasingly complicated. Enterprises are growing more concerned that they might be attacked via their supply chain.

According to a report from the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), one of the top five causes of cybersecurity breaches is supply chain attacks.These fears are warranted. It has become widely recognized that data breaches related to the supply chain have increased significantly. According to a report from the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), one of the top five causes of cybersecurity breaches is supply chain attacks.1

One high-profile example of such an attack was reported on 7 May 2024 when the British Ministry of Defense (MOD) suffered a data loss affecting as many as 272,000 UK service personnel. Defense Secretary Grant Shapps confirmed that the data breach resulted from a compromise involving the contractor Shared Services Connected Ltd (SSCL).2 This raises the question of how much effort the UK Ministry of Defense (MOD) is putting into conducting thorough due diligence for its supply chain risk assessments. Moreover, if the MOD finds itself unable to navigate the increasingly intricate maze of supply chain, it begs the question: How are smaller enterprises supposed to be equipped to do so? Answering this question requires an understanding of potential threats and their resulting risk.

A highly effective way for an organization to demonstrate to stakeholders that data and information are not at risk due to the supply chain is to gain the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 27001 certification,3 which can be certified by an approved accreditation body.4 ISO 27001 is an international standard that provides a framework for the implementation and management of an information security management system (ISMS). Elements of this standard address the need for information security controls to ensure that an organization’s suppliers have adequate protections in place. Included in the controls of ISO 27001 is Annex A Control 5.7–Threat Intelligence, which focuses on collecting information about the threats an organization might face. This control is of particular importance because it can enable senior leadership to make better decisions and ultimately tackle the complex web of the supply chain.

The messy web of supply chain complexities can open the door for adversaries to gain access to an organization, its assets, and its data.Uncovering the Hidden Strands in the Web

According to guidance on supply chain security from the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC),5 the first principle of supply chain security is to understand the risk. An organization must understand the value of its assets and information and the sensitivity of the contracts it will establish with its suppliers. To achieve this, the organization must review its suppliers, identify potential risk, assess the identified risk, and implement appropriate risk mitigation strategies. However, this can be a time-consuming process, especially when organizations are increasingly outsourcing more products and services (figure 1), creating the need for additional risk assessments.

Another consideration is that to understand risk, all enterprise risk must be recorded in a risk register, but risk managers cannot protect against unidentified risk. In the process of identifying their suppliers, organizations may inadvertently overlook certain vendors. This oversight can lead to a failure to recognize potential risk and attack vectors from their supply chain.

Additionally, when identifying risk, organizations must consider all laws, regulations, and standards with which they must comply. These will vary between both countries and industries. For example, US-based healthcare enterprises must comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA),6 which aims to help maintain medical patient privacy. Similarly, any organization that targets or collects data related to those living in the European Union must comply with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), described as “the toughest privacy and security law in the world.”7

This is where the ever-expanding spider web that is supply chain risk assessment begins to tangle, complicating the process for already overburdened enterprises. How is an organization supposed to begin planning a risk treatment program if it cannot get through the tangled web surrounding its risk assessments in the first place? To start teasing the knots out, enterprises and their directors must accept that they will never be perfect and that there is no such thing as zero risk. Leaders should begin by looking at the overall picture of their organization to understand the threats it faces—and the corresponding risk. Committing to continual improvement will help enterprises adapt as their profile changes (and ideally matures) over time.

To Prevent Attacks, Cut No Corners

To confront supply chain obstacles, organizations must first remember why they need to tackle the spider’s web of complexities. Their reason for assessing their supply chain risk may be to achieve compliance with a standard such as ISO/IEC 27001. But this is not the only reason an organization should prioritize investigating its supply chain. There are also cost and time savings to be gained from implementing preventative strategies, which are cheaper and more effective than reactive strategies.

Consider this example. Attackers often bypass direct defenses by targeting overlooked vulnerabilities in the supply chain, much like historical military strategies that exploited unguarded borders. For instance, during World War I and II, invading forces often bypassed heavily fortified areas to strike through less defended regions. In the same way, many organizations investigate their internal functions and stakeholders but overlook external stakeholders such as their suppliers, customers, partners, and vendors. Adversaries often use such oversights to gain access to the organization by exploiting the vulnerabilities of its suppliers or customers. These stakeholders often possess sensitive information about organizational systems or processes, which could inadvertently give cybercriminals the keys to exploit and attack an organization. The messy web of supply chain complexities can open the door for adversaries to gain access to an organization, its assets, and its data.

Some Suppliers Are Like Borders, They Cannot Be Changed

Sometimes a risk owner decides that a supplier’s practices pose too great a risk to the organization in question. In these cases, a decision might be made to avoid the risk by switching suppliers. However, this is not always an option. In the same way that France cannot avoid having a border with Belgium, some suppliers cannot be changed, and thus the supply chain web cannot be unraveled.

Two recent examples of suppliers affected by ransomware attacks include county councils and water companies. In March 2024, Leicester City Council experienced a ransomware attack8 similar to what Southern Water experienced in January 2024.9 Unfortunately, the customers of these two companies cannot simply avoid the risk and switch providers, because water companies and city councils are assigned to consumers and enterprises by their location. Thus, they need to find other controls that can treat and reduce the risk to an acceptable level. One option would be to employ additional monitoring of high-risk suppliers, utilizing threat intelligence to inform senior leadership, and examining how this affects the overall risk level of an organization.

Threat Intelligence Can Simplify a Complicated Web

Applying threat intelligence may seem like yet another expansion of the sticky supply chain web that organizations must factor in. Some organizations mistakenly believe that the threat landscape cannot be monitored; however, there are endless possibilities for organizations to implement threat intelligence, otherwise known as Control 5.7 of the ISO/IEC 27001 standard. If an enterprise is unable to conduct threat intelligence, many cybersecurity enterprises offer threat intelligence as a service. Perceptions often exist that threat intelligence requires sophisticated solutions, but this does not need to be yet another web to get tangled up in. The simplest thing to do is to employ threat intelligence as a service, conducted by an intelligence analyst (i.e., a human, not a tool) who uses simple resources (e.g., social media, data breach sites, news reports, open-source intelligence (OSINT) platforms) along with expert knowledge to tailor the threat intelligence to the individual enterprise. Threat intelligence analysts can assess supplier risk based on the likelihood of the risk coming to fruition and the impact that it would have on the organization in terms of financial loss, reputational damage, data safety, and other potential consequences. These analysts can then work with risk practitioners to choose suitable controls that help reduce the risk to the enterprise in alignment with business objectives.

Threat intelligence should be documented in a report that addresses strategic, tactical, and operational intelligence. This will help ensure that the enterprise is prepared for an ISO/IEC 27001 audit.

Staying on Top of Standards

The supply chain web is made more challenging by the complexity of standards and regulations. ISO/ IEC 27001 serves as an example, with its many clauses that may seem like they are adding more knots to the supply chain web. However, to make risk management less of a burden, organizations can break this standard down by referencing the most relevant clauses first. In this way, organizations can parse complex standards into manageable components and effectively manage their supply chains using a fit-for-purpose approach.

For example, organizations should be aware of Clause 6.1.2 C of ISO/IEC 27001, which states, “The organization shall define and apply an information security risk assessment process that: identifies the risks.”10 This can be traced back to Clause 4 of ISO/IEC 27001, “Understanding the organization and its context.”11 An organization must identify the interested parties that are relevant to an information security system and the internal and external factors that may affect it, such as suppliers.

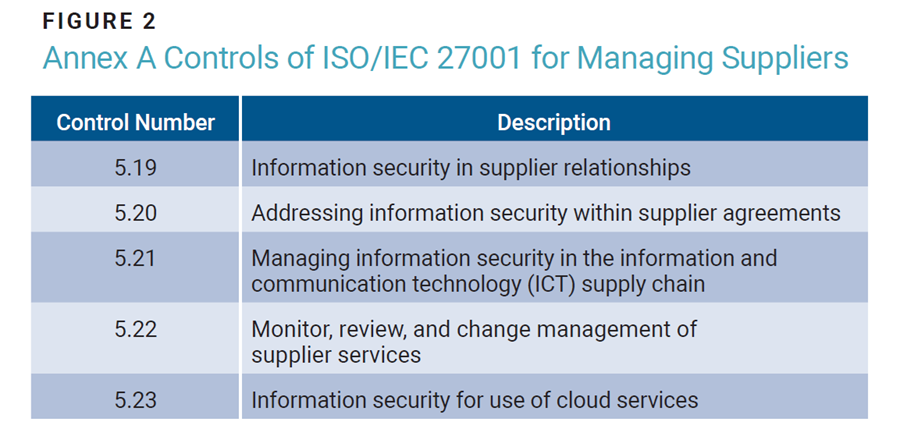

While ISO/IEC 27001 may feel like it is adding complexities on top of complexities, it ultimately simplifies organizational processes. The standard has a whopping 93 controls, but besides Annex A Control 5.7–Threat Intelligence, which is a key step in the risk identification phase, there are only five controls that risk managers must consider when managing supply chain risk (figure 2). This is because these controls focus specifically on suppliers.

Identifying Types of Suppliers

No two enterprises are alike, but organizations should consider the following types of suppliers when identifying potential risk.

- Critical suppliers

- Contractors

- Transactional suppliers

- Partnership suppliers

- IT support

- Human resources

- Utility providers

- Hardware and software

Critical suppliers are the ones an enterprise needs to carry out its operations, thus, it is best practice to examine those suppliers first. For example, the manufacturing industry relies on subcontractors who manufacture the components of the goods that the manufacturer produces. If the subcontractor were to be hit with ransomware and unable to produce the components, it would impact a manufacturer’s ability to fulfill customer orders.

Similarly, it has become increasingly common for organizations to outsource services such as IT support and human resources (HR) activities, which may involve processing sensitive enterprise data. If the outsourced service provider were breached, the attackers could gain access to the original enterprise’s sensitive data via that supplier.

Avoid Getting Stuck in the Supply Chain Web

One of the most effective ways for organizations to spare themselves from becoming knotted in the supply chain web is to plan actions to address risk. When planning to achieve ISO/IEC 27001 certification and preparing for the subsequent audit, it must be ensured that the information security management system can achieve its intended outcomes, prevent or reduce undesired effects, and achieve continual improvement. Each enterprise should have its own unique plan; however, several recommendations can enable organizations to plan their directions of travel:

- Gain the support of top-level management for the proposed risk identification, assessment, and treatment program.

- Identify critical suppliers and ensure that there are alternatives in case they cannot provide a service.

- Ensure that there is documentation of the results of risk assessments. Auditors value well-documented evidence.

- Implement ISO/IEC 27001 Annex A Control 5.7–Threat Intelligence, which will provide an overview of the threat landscape and help management make decisions about mitigating risk.

- Set aside time for identifying and assessing risk in the supply chain. This will make the process feel less overwhelming and make preparing for audits achievable and manageable.

- File suppliers’ invoices in a clearly labeled and secure file structure, ensuring that they are accessible to those who require them.

- Annually send suppliers evaluation forms to complete. Questioning them about their certifications; whether they meet standards (e.g., ISO/IEC 27001); and if they have NCSC-accredited certificates such as Cyber Essentials or Cyber Baseline12 in place. This will require enterprises to demonstrate their due compliance and reduce the requirement for audit suppliers.

- When organizations have certifications in place, check what part of the organization is in the scope of the certification in question. Sometimes only certain elements of the enterprise will be in the scope of the certification rather than the entire organization.

- Utilize risk assessment tools (there are many low-cost tools available). These tools can record and calculate the inherent and residual risk levels once risk treatment has been applied. Such tools can also demonstrate performance metrics as part of the risk treatment program.

- Check with the finance team for outgoing payments to ensure no suppliers have been overlooked.

- Pay special attention to utility providers and their corresponding county, district, and local councils, because they are tied to a location that cannot be changed. Thus, alternative controls may be required to reduce risk, such as additional threat monitoring.

- Implement a continuous improvement culture within the enterprise, recording changes as they are made. These improvements can then be demonstrated to top-level management.

Conclusion

The supply chain is complicated due to a combination of factors, such as more enterprises outsourcing processes and services for efficiency, so the process for understanding their supply chains can seem daunting. Additionally, the threat landscape and an organization’s risk profile change over time, so enterprises do not always recognize when they are vulnerable or if a new risk has arisen. When organizations begin working to implement standards such as ISO 27001, the implementation can appear to be yet another tangle to unpick. However, ISO 27001 is indeed part of the solution, as it is a way to demonstrate to stakeholders that processes and controls are in place to protect the supply chain.

Despite the expanding supply chain web, organizations need not feel overwhelmed. It can be untangled in small steps. The path forward requires that organizations aim for the continuous improvement of their overall risk culture. Senior directors and top-level management must accept that their risk level will never be zero. However, there is much to be gained from establishing an overall risk appetite and identifying what an acceptable risk level looks like within their business model. This can be achieved by utilizing thorough threat intelligence measures. Taking these first steps will make the web less tangled and reduce the risk of an organization being attacked via its supply chain.

Endnotes

1 Information Commissioners Office, “Organisations Must do More to Combat the Growing Threat of Cyber Attacks,” 10 May 2024, United Kingdom

2 Wilcock, D.; “Grant Shapps Says ‘Potential Failings’ by Contractor SSCL May Have Made Mod Payroll Hack ‘Easier’ as China is Blamed for Cyber-Attack on Armed Forces Personnel Data,” Daily Mail UK, 7 May 2024,

3 International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), ISO/IEC 27001:2022

4 Accreditation bodies vary by country.

5 National Cyber Security Centre, “Supply Chain Security Guidance: Understand the Risks,” United Kingdom

6 US Department of Health and Human Services, “HIPAA for Professionals,” USA

7 Gdpr.eu, “What is GDPR, the EU’s New Data Protection Law?,” European Union

8 BBC News, “Leicester: Personal Data Shared Online After Cyber-attack – Council,” 3 April 2024

9 Southern Water UK, “Cyber Attack —Update for Customers”

10 ISO/IEC, ISO/IEC 27001:2022

11 ISO/IEC, ISO/IEC 27001:2022

12 Enterprises in the United Kingdom that possess the Cyber Essentials certificate can be identified at https://iasme.co.uk/cyber-essentials/ncsc-certificate-search/. Enterprises outside of the United Kingdom that possess the Cyber Baseline certificate can be identified at https://iasme.co.uk/iasme-cyber-baseline/certificate-search/.

HANNAH HUNT | CISM, ISO 27001 LEAD IMPLEMENTER

Is the head of threat intelligence at The Armour Group of Companies. She has 15 years of experience in defense, intelligence, governance, risk management, compliance, and physical, information, and cybersecurity.