Supply chain management research often focuses on identifying the weakest link in the supply chain and trying to replace or repair it. However, recent research on the NotPetya attack suggests that there is more that organizations can do to minimize damage from an IT supply chain attack. First, they must take a broader view of the effects caused by such attacks.

The weakest link theory proposes that a chain will break at the weakest link.1 Subsequently, when any link is broken, the chain is not functional until the link can be repaired or replaced. Extending this theory to IT supply chains, the weakest link theory states that organizations are exposed to direct attacks on their IT assets and attacks on other IT elements along the entire supply chain. No matter how well protected an organization’s IT assets are, they are exposed to the risk of production or service disruption due to infection from the least protected network participants.2 Therefore, the reliability and safety of the entire IT supply chain depends on the partner with the least secure, or most vulnerable, IT system, since cybercriminals must break only one link in the chain disrupt the entire supply chain’s production capacity.

Organizations have tried to use this concept to make stronger chains, but much of the existing supply chain cybercrime literature focuses on reputational damage and litigation costs caused by the data breaches. A recent study of the 2017 NotPetya attack3 provides much more insight into the financial effects on the supply chain. By exploring the causes of the attack and the negative financial effects, organizations can prepare for future cyber-related production disruptions due to effects caused by weakest link failures.

The longer indirect customers are attached to the directly affected customers, the more dramatic the negative effects of the event will become. This requires organizations to examine their IT supply chains and identify how to quickly detach themselves in the event of a cyberattack.NotPetya Attack

In 2016, a ransomware attack (Petya) was circulated using the .pdf file attachments of a potential job applicant.4 Once the .pdf attachment was opened, the ransomware encrypted the user’s master file table and rendered the user’s data unreachable. Users were required to make a Bitcoin payment to get their hard drives decrypted. In June 2017, a similar attack was launched using NotPetya. However, unlike Petya, which focused on financial gain, NotPetya’s intent was to shut down Ukrainian banks, organizations, and the Ukrainian government. This attack has since been attributed to a Russian military intelligence group.5 The most alarming aspect of this attack was how it used a leaked code, EternalBlue, to move from one network to another. The EternalBlue code was able to find network administrator credentials stored in individual machines.

The NotPetya attack targeted a tax accounting software used by Ukrainian organizations to file taxes with the Ukrainian government. This software was widely used across Ukraine, leading to infections in most enterprises that utilized it.6 Many international organizations with Ukrainian connections were infected as well. The effect was devastating, as the focus of the attack was not on ransom, but on dismantling production. The decryption keys for the affected machines were not tracked by the attackers.7 Rapid recovery was therefore not possible for those infected.

Due to the financial effects of this supply chain attack, Crosignani, Macchiavelli, and Silva conducted a study to further investigate the extent of the damage.8 Their study identified enterprises who were directly affected by the attack. The study also used global supply chain data to identify 233 customers and 320 suppliers who were indirectly affected by the strike. These enterprises were added to the list of those who were directly affected, and balance sheet and income statement information was collected on all organizations. Finally, loan-level information was collected.9

Results from this study showed a significant negative financial effect on the customers of the enterprises who were directly affected. This propagation of profit loss for customers was confirmed when comparing their results with similar enterprises that were not affected by the attack. The study estimated a 1.3-point drop in earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT).10 The result was an estimated US$1.8 billion in losses for directly affected enterprises and an additional US$7.3 billion in losses for indirectly affected supply chain customers.11 Supporting existing supply chain literature, losses to downstream organizations were higher than losses to enterprises directly affected by the attack.12

This study also revealed new insights into what makes organizations more vulnerable to disruptions caused by attacks. Enterprises who could not easily substitute a service or product were affected more than those that had options for substitution. Similarly, enterprises that produce more specific products or services create greater disruptions for their customers than those that produce non-specific goods. A second variable that affected the enterprises’ ability to weather the storm associated with the loss in profit was internal liquidity and borrowing power. Financial data showed enterprises used both internal liquidity and external borrowing to overcome the negative effects of the cyberattack. This resulted in an estimated 1% increase in long-term debt over total assets compared to unaffected firms.13

Varying Impacts of IT Supply Chain Attacks

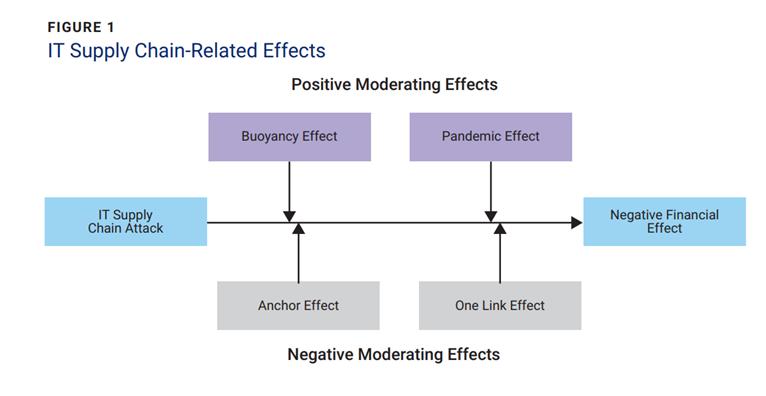

Based on these results, it is likely that supply chain cyberattacks are more complex than a weak link in the chain. Analysis of these results shows four effects associated with IT supply chain attacks (figure 1). These effects are connected to the concept of the weakest link but go much further in explaining the effects on the IT supply chain. These four effects are the:

- Anchor effect

- Only-one-link effect

- Buoyancy effect

- Pandemic effect

Anchor Effect

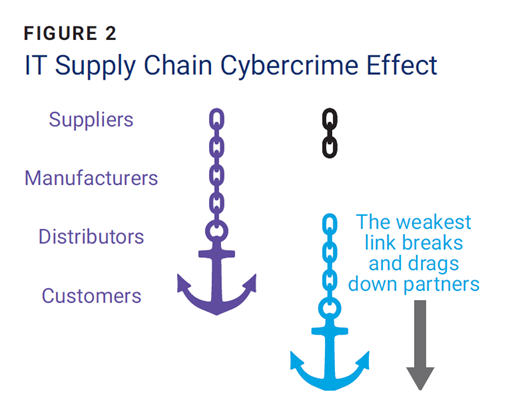

Many organizations view the supply chain as horizontal: Suppliers move goods to producers, who, in turn, move the finished product/service to the customer. However, research on the NotPetya attack shows that an IT supply chain is more accurately viewed as a chain connected to an anchor (figure 2). The suppliers are located near the top and the customers are the anchor. When one of the links in the chain breaks, all the links still connected to the anchor are negatively affected.

The NotPetya attack resulted in an estimated US$1.8 billion loss for directly affected customers.14 In contrast, the attack resulted in an estimated US$7.3 billion loss for indirectly affected customers.15 Enterprises downstream of the broken link are therefore impacted while they try to support the customer. Thus, organizations must find ways to disconnect from the falling anchor. The longer indirect customers are attached to the directly affected customers, the more dramatic the negative effects of the event will become. This requires organizations to examine their IT supply chains and identify how to quickly detach themselves in the event of a cyberattack.

The study also showed that upstream members in the chain did not suffer the same effects as the members downstream of the broken link.16 For example, a supplier who provides material to a manufacturer who is attacked will not be as negatively affected as a distributor who is provided with finished products by the directly affected manufacturer. This is further demonstrated by the anchor effect, wherein the links between the broken link and the customer are dragged down by the anchor, while those upstream are no longer connected to the end customer and do not receive the same level of negative impact.

The ramifications of such an attack are long lasting and not easily forgotten by the organizations who experience them. The temporary disruptions caused by the NotPetya attack significantly eroded the relationships between the customers and suppliers. This likely caused customers to find alternative IT supply chain partners after the event.17 A study of the NotPetya attack showed that affected customers were likely to end their trading relations with suppliers who were directly affected by the attack. For example, Tesla’s chief executive officer (CEO) Elon Musk recently revealed that CrowdStrike had been deleted from all systems after the 2024 CrowdStrike outage.18 This highlights the negative effect on the weakest link.

Losing any link in the chain has the possibility of affecting the entire IT supply chain if the enterprise provides a service/product that is not easy to duplicate.Only-One-Link

Effect One way to ensure that the anchor does not fall to the bottom of the ocean is to ensure that there are multiple links at the most vulnerable locations in the chain. Adding an additional link, or a redundant link, allows one link to break and the redundant link to become the primary link. For example, consider an enterprise that has both a primary and a backup means of processing payments. Research shows that organizations with only one partner were the most affected by cybercrime.19 Identifying the weakest links in the IT supply chain and adding a second vendor/supplier/provider significantly decreases the chance of negative effects, since the anchor (customer) is still connected to the chain in the event of one link in the chain breaking.

The only-one-link effect is even more significant when there are few providers worldwide. Increased dependence on one firm that provides a large market share creates a situation that organizations should try to avoid.20 This was evident during the 2024 CrowdStrike outage that affected upwards of 45% of the Fortune 100 companies.21 The post-mortem of the CrowdStrike outage showed that the problem stemmed from a hole in the testing software that caused the content validation tool to miss an error in the defective Channel File 291 content update. The flawed configuration update was pushed to users, which caused operating systems to crash due to a logic error. Microsoft estimated that more than 8.5 million Windows devices had been affected based on crash reports.22

The anchor effect and only-one-link effect illustrate the negative aspects of supply chain links. The remaining two effects, buoyancy and pandemic, refer to what organizations can do to help mitigate the negative effects of supply chain IT failures.

Buoyancy Effect

Organizations with sufficient financial liquidity, or borrowing power, stay afloat longer than those operating on a constrained financial budget. Enterprises with significant liquidity and borrowing power were able to maintain investments and avoid negative impacts on employment, despite the NotPetya attack.23 This availability of funds acts as a lifejacket and helps overcome the initial shock of the attack. Organizations that are significantly financially constrained may not recover from the attack and instead be forced to shut down. Losing any link in the chain has the possibility of affecting the entire IT supply chain if the enterprise provides a service/product that is not easy to duplicate.

Pandemic Effect

Research has shown that organizations are willing to forgive breaches in the IT supply chain if a large percentage of providers are affected by the strike. For example, during an event such as a pandemic, there is an overall perception that most organizations have been affected and therefore there is often less incentive to take action against supply chain partners who are attacked. Therefore, providers/suppliers with a larger market share may not be as susceptible to supply chain partners leaving them as organizations who have a smaller market share.

Minimizing the Effects of Cybercrime on the IT Supply Chain

Further analysis of the research shows there are four major ways firms can minimize the negative effects of IT supply chain attacks and possibly bolster the positive moderating effects. These actions are:

- Avoid being the weakest link—The negative effects are greatest for the weakest link. Organizations should spend the majority of their time and budget finding ways to strengthen internal systems and training employees. Conduct audits to determine which systems have the greatest risk of being attacked. Where possible, develop internal products that outsiders cannot access. Consider replacing the most vulnerable systems with internal products.

- Disconnect quickly—Develop contingency plans that include methods of disconnecting from other members of the IT supply chain. To decide if operations should continue or pause, measure risk to the enterprise and its customers. Contingency plans should include the appropriate corrective actions, which range from continuing normal operations to suspending operations quickly if conditions warrant.

- Identify where there is only one link—Review the IT supply chain and identify where there are minimal providers, or just one. Gone are the days of mapping the entire chain of members and their software systems. Research shows that the average number of external software applications and platform services for Fortune 2000 companies increased from 1,100 in 2016 to 7,000 in 2024.24 There are too many single applications to track. Instead, ensuring redundant links may be more beneficial for the supply chain. This should include identifying raw materials, physical products, services, distributors, or software applications that are critical to daily operations. Organizations use interconnected operational technology, meaning software issues can affect multiple systems. For example, a Delta Airlines software application used to track flight crews became inoperative due to the 2024 CrowdStrike outage.25 To avoid situations such as this one, spend time before the attack setting up alternative partners. This should include testing links before any attack. Adding members/services may seem counterintuitive, since each addition increases the overall probability of an attack affecting the enterprise. However, duplicate links in the chain ensure that the anchor does not fall when one link breaks.

- Review liquidity and borrowing power—Surviving an IT supply chain attack requires financial resilience to weather the storm. If the organization has enough funds to cover the initial losses, there is a better chance it will endure the immediate effects of the attack. This should also include a financial stability review of partner organizations. A financially unsound link in the chain could negatively impact partners if the single link can no longer participate in the supply chain.

Conclusion

IT supply chain attacks will continue to occur and can be more unpredictable than other contingency planning events, such as natural disasters or economic changes. IT events often happen more quickly and affect a larger geographic area. Thus, planning for an IT supply chain attack becomes much more important, since there is less time to respond and the effects can be greater.

Enterprises should shift focus away from evaluating only the weakest links in the IT supply chain to looking at the four combined effects caused by a failure in the weakest link. Focusing on mitigating the negative effects associated with the anchor effect and only-one-link effect can minimize the overall negative impact of an attack. Meanwhile, organizations should buffer themselves with financial liquidity and credit options to increase their buoyancy effects. Last, there will continue to be IT supply chain effects, and organizations should acknowledge the pandemic effects they will have to endure. This does not remove the responsibility from preparing for them, but rather fosters a realization that even strong links in the supply chain will be affected by IT supply chain cybercrimes. Preparing for these events now can mitigate damage later.

Endnotes

1 Slone, R. E.; Mentzer, J. T.; et al.; “Are You the Weakest Link in Your Company’s Supply Chain?,” Harvard Business Review, September 2007

2 Kunreuther, H.; Heal, G.; “Interdependent Security,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, vol. 26, p. 231–249, 2003

3 Crosignani, M.; Macchiavelli, M.; et al.; “Pirates Without Borders: The Propagation of Cyberattacks Through Firms’ Supply Chains,” Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 147, iss. 2, p. 432-448, 2023

4 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

5 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

6 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

7 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

8 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

9 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

10 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

11 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

12 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

13 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

14 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

15 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

16 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

17 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

18 Turner, N.; “Musk Says He’s Deleted CrowdStrike From Systems After Outage,” Bloomberg, 19 July 2024

19 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

20 Podeswik, D.; The Pitfalls of Supply Chain Risk Management,” ISACA® Journal, vol. 3, 2022

21 George, A. S.; “When Trust Fails: Examining Systematic Risk in the 2024 Crowdstrike Outage,” Partners Universal Multidisciplinary Research, vol. 1, iss. 2, p. 134-152, 2024,

22 Staff, C.; “CrowdStrike Failure: What You Need to Know,” CIO, 1 August 2024

23 Crosignani; “Pirates Without Borders”

24 George; “When Trust Fails”

25 Ashare, M.; “Delta’s CrowdStrike Recovery Stymied by Crew-Tracking Systems Failure,” CIO Dive, 22 July 2024

GERALD F. BURCH | PH.D.

Is an assistant professor at the University of Florida (Pensacola, Florida, USA). He teaches courses in information systems and business analytics at both the graduate and undergraduate levels. His research has been published in the ISACA® Journal and several other leading peer-reviewed journals. He has helped more than 100 enterprises with his strategic management consulting and can be reached at gburch@uwf.edu.

JORDAN BURCH

Is the chief technology officer at Foster Care to Success, where his focus is monitoring system availability, logging system event data, and reporting. He has implemented monitoring platforms for both the private and public sectors, including entire state digital infrastructures and international pharmaceutical and agricultural ventures. Burch has a strong background in network engineering and the difficulties faced by large enterprises attempting to collect usable system statistics from the far reaches of their infrastructures. He is involved in projects related to the Internet of Things, wherein he collects data from embedded systems that allow greater visibility of environmental factors at a much larger scale. He can be reached at https://www.linkedin.com/in/jordanburch/.

JOSHUA BROWN

Is a senior application security manager. His primary role is managing application security across multiple domains. He works with developers, DevOps, and internal security teams to integrate security in the application delivery life cycle and ensure that software delivery meets regulatory requirements and best practices. He can be reached at joshb910@gmail.com.