According to the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA), continuous auditing is a new paradigm that shifts from periodic evaluations of risk factors and controls based on a sample of transactions to ongoing evaluations based on a larger proportion of transactions.1 This methodology is a natural fit for retail lending businesses. Retail lending, especially credit card lending, has been digitalized more progressively than other parts of the banking sector, accelerating its data readiness for continuous auditing. In addition, both the first and second lines of defense in retail lending employ statistical techniques (e.g., scorecard modeling) to support decision making. As the third line of defense, the audit field must adopt a more continuous approach to catch up. There is, however, one domain within retail lending that is more subtly suitable for continuous auditing: credit line management. While credit line management itself is not the primary responsibility of internal auditors, it presents unique complexities for auditors that necessitate more proactive and continuous monitoring. By adopting this approach, auditors can more smoothly navigate complexities and provide more timely and valuable insights to the first and second lines of defense.

Credit Line Assignment

In the competitive retail lending arena, credit line assignment is key. Typically, an initial credit line is assigned to a borrower approved by the bank’s underwriting process, with follow-up adjustments made based on profitability and risk management factors. There are certain negative effects of poorly managed credit line assignments:

- An increased credit line for borrowers without the financial capacity to handle a new, higher credit limit may cause an unexpected level of credit loss.

- Regulatory concerns can arise if borrowers are induced to carry unaffordable and persistent debt due to imprudent credit line increases.

- A credit line decrease or suspension might irritate borrowers, who may view their assigned credit lines as a status symbol or indication of value. As a result, they may file complaints to regulators or choose to default on future payments.

Audit Concerns and Challenges Related to Credit Line Management

Auditors reviewing credit line management at retail banking enterprises must take into account the adaptive (challenger/champion) approach used by banks to test, review, and implement credit line strategies: a new strategy (the challenger) is run in parallel with the existing strategy (the champion) on the same target customer segment to obtain validation before broad implementation. Some of the challenges auditors may have to navigate are:

- Iterative refinement—Each iteration of a strategy serves as useful input for fine-tuning the next iteration. As long as it adheres to established standards and procedures, a single iteration that fails to achieve its intended goals is not necessarily an issue.

- Extended time frames—Challenger/champion strategies may take several months to a year or more to provide results as borrowers repay or default on their debts according to the agreed-on schedules. Auditors may experience longer project durations than usual.

- Emerging risk—The implementation of challenger/champion strategies requires continuous experimentation with customer segmenting, targeting, and credit terms, which may be different from existing credit criteria and standards. Hidden risk factors and vulnerabilities may emerge.

Toward a Continuous and Intelligent Auditing Approach

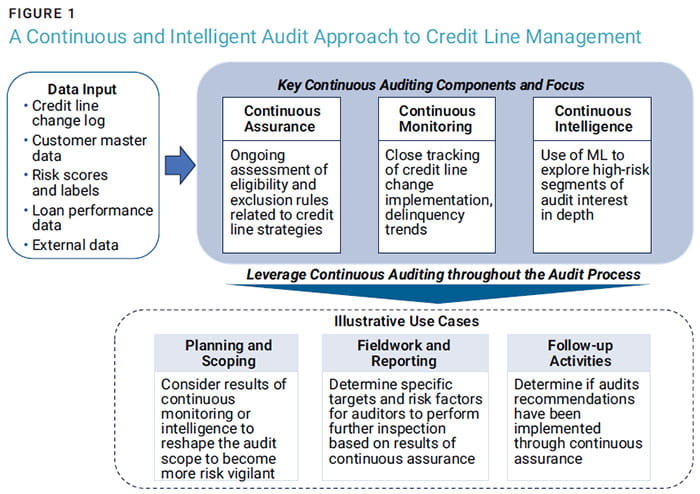

Credit loss is an unavoidable part of the lending business, and an expected level of loss is factored into the interest charged to borrowers. It is the unknown and unexpected credit loss due to poor credit line management that should be the auditor’s focus. To tap into this unknown risk, auditors require a more hybrid and intelligent approach that consists of three components:

- Continuous assurance—Ongoing rule-based assessment for baseline control assurance

- Continuous monitoring—Closely tracking implementation and performance of credit line strategies based on metrics of audit focus

- Continuous intelligence—Using machine learning (ML) to identify high-risk segments and explore characteristics of audit interest beyond auditors’ prior knowledge

All three components can be seamlessly incorporated into all phases of the audit process (figure 1).

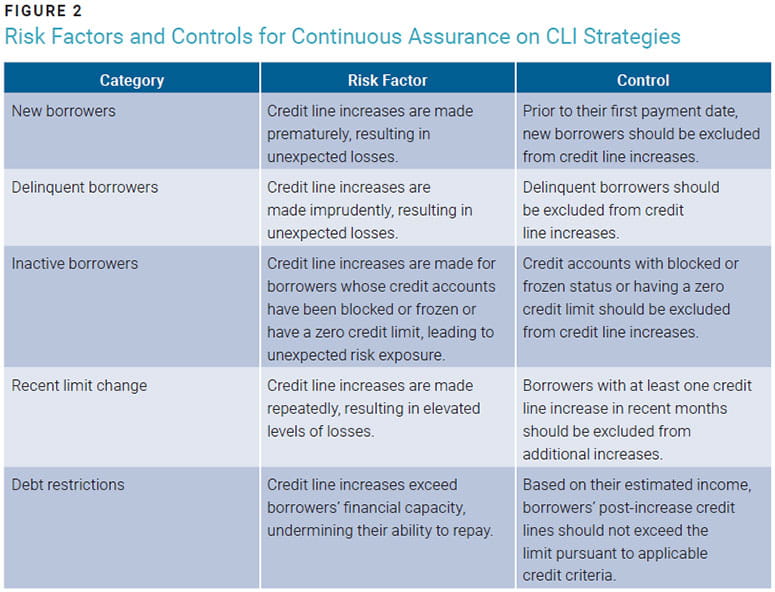

Continuous Assurance

Credit line strategies are subject to certain constraints. For example, in the United States, a credit line increase (CLI) must be supported with documentation of the borrower’s ability to pay.2 In addition, banks apply a suite of eligibility and exclusion rules. These rules are usually implemented as automated controls in the bank’s account management process and can be incorporated into continuous assurance strategies. Figure 2 provides an example.

Continuous Monitoring

There are two components of monitoring for auditors to comprehensively assess credit line management risk.

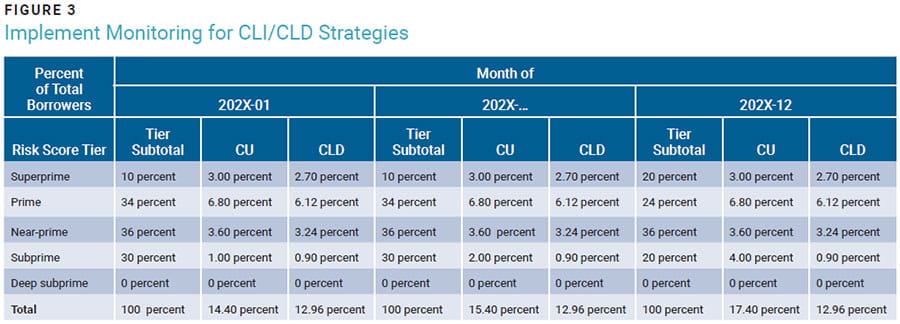

Implementation Monitoring

This process evaluates whether CLIs and credit line decreases (CLDs) have been appropriately implemented and are being used as intended. Such monitoring should be carried out periodically, with a frequency appropriate to the bank’s risk profile and appetite. Figure 3 illustrates the monthly monitoring of the following factors:

- Metrics—Credit score distribution of subpopulations subject to CLIs and CLDs versus the entire portfolio for the same period

- Auditor focus—Whether the CLI/CLD-related risk score distribution matches the bank’s risk appetite and target segmentation, and if not, whether it is supported by solid business decisions for the respective CLI/CLD campaigns

Notes: Tier subtotal is the percentage of borrowers in each risk score tier out of the total number of borrowers in the portfolio during the relevant month; CLI is the percentage of borrowers in each risk score tier that received an increase; CLD is the percentage of borrowers in each risk score tier that received a decrease.

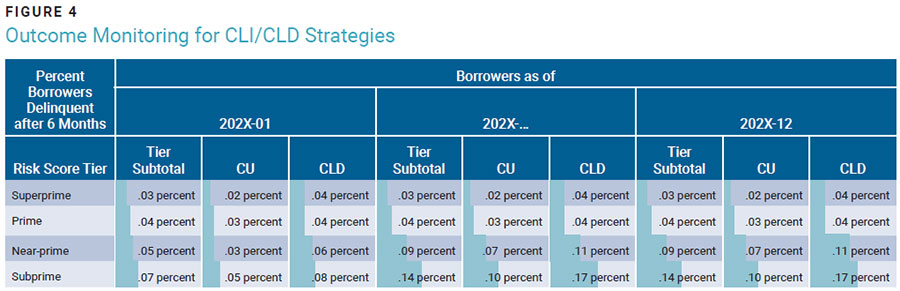

Outcome Monitoring

This process validates whether credit line strategies are performing as intended. One key focus for auditors is delinquency, which is the leading indicator of credit loss. Depending on how long it takes for delinquency to occur after each CLI/CLD campaign, a performance window should be appropriately defined. Figure 4 illustrates a six-month performance window based on the following factors:

- Metrics—Delinquency ratio among risk score tier subpopulations subject to CLI/CLD versus the entire portfolio for the same period

- Auditor focus—Auditors should evaluate: (1) whether there is a monotonic delinquency trend across different credit risk score tiers within the same batch of CLI campaigns (e.g., delinquency consistently decreases as borrowers move toward the better score tiers, and vice versa); (2) within each risk score tier, whether CLI borrowers consistently perform better than the tier average while CLD borrowers perform worse than the tier average. (Generally, better-performing borrowers are given CLIs, while underperforming or at-risk borrowers from target segments are given CLDs.) If either answer is no, auditors should investigate the implementation and supporting analysis of the relevant CLI/CLD campaign.

Notes: Tier Avg. is the percentage of borrowers in each risk score tier that have become delinquent after six months; CLI is the percentage of CLI borrowers in each risk score tier that have become delinquent after six months; CLD is the percentage of CLD borrowers in each risk score tier that have become delinquent after six months.

Continuous Intelligence

Advances in artificial intelligence and ML have allowed auditors to explore risk factors that were traditionally hidden. The following four-step process uses a basic ML algorithm called a decision tree that automatically segments high-risk borrowers:

- Data input—A target variable is defined by the delinquency status of a borrower in the performance window (e.g., if the borrower has ever been delinquent for a certain number of days within six months of the last CLI). Information about the borrower’s behavior, preferably related to CLI strategies (e.g., prior and current balance or annual percentage rate, credit score, delinquency history), is used as input to facilitate the segmenting of individual borrowers.

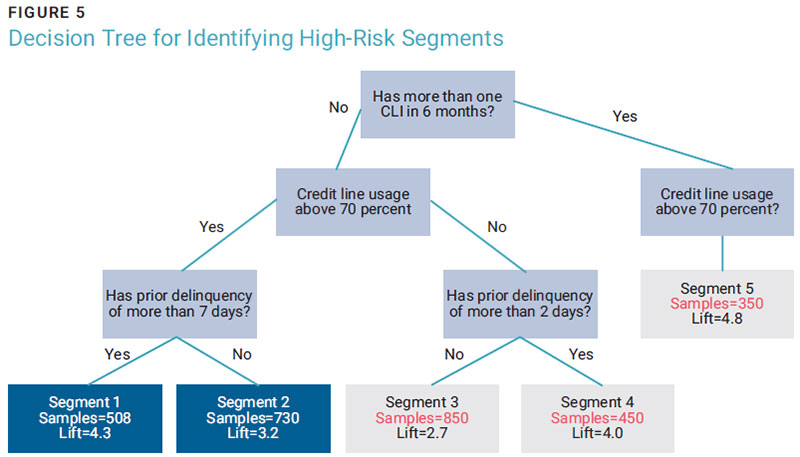

- Tree splitting—This step creates a decision tree by using binary splits among the input features. The output is a structure of nodes, each hosting a group of borrowers. Each node is either a leaf node or a split leading to further leaf nodes. These splits are chosen by an algorithm programmed to maximize the homogeneity of borrowers in each node. Figure 5 provides a simplified example of splitting borrowers based on three features (CLI frequency, credit line usage, and past delinquency), resulting in a total of five leaf nodes.

- Pruning—Once a tree has been established, each leaf node is evaluated and selected in a mechanism called pruning. For purposes of identifying high-risk CLI-related segments, the following evaluation criteria are proposed:

- Each node contains a minimum number of samples (i.e., borrowers). (Note: if this threshold is set too low, the results from the decision tree might not translate into meaningful business information.)

- Each node presents a higher-than-threshold lift value—that is, the delinquency rate of samples in the leaf node divided by the delinquency rate of the entire portfolio. (Note: A lift value of 3 or higher is preferred to ensure that only truly highrisk segments are identified for follow-up.)

Nodes that do not meet either of these criteria are “pruned,” or discarded from segments for audit follow-up.

In figure 5, the thresholds of minimum sample size and lift value are defined as 500 and 3, respectively, for illustrative purposes. Consequently, leaf nodes related to segments 3–5 are discarded (with their unqualified criterion highlighted in red), while segments 1 and 2 will be subjected to further audit follow-up.

- Alignment—Continuous intelligence can collaborate with the other components of continuous auditing. For example:

- Auditors can investigate the high-risk segments identified earlier for consistency with relevant credit criteria. If there are exceptions in the implementation of credit criteria, they can be incorporated into continuous assurance.

- High-risk segments can be added as a risk score tier in continuous monitoring. This helps auditors track how high-risk segments are addressed by future credit line strategies on an ongoing basis.

Deploying Continuous Auditing

Key takeaways from the author’s experience with deploying continuous auditing include:

- For continuous assurance and monitoring—Audit rules and metrics, derived from insights of the first and second lines of defense in credit line management, should ideally be embedded into risk engines and systems. This allows auditors to receive timely updates as credit line management activities progress.

- For continuous intelligence—This exploratory process relies on an ML platform, which can be leveraged for internal audit functions with appropriate access controls to ensure data security.

But most important, the successful deployment of continuous auditing depends on seamless collaboration between internal audit and other functions, including product, risk, and technology teams.

Conclusion

As credit line management activities constantly iterate to keep the bank competitive in the market, auditors must evolve in parallel to remain relevant and effective in this dynamic realm. Continuous auditing fits perfectly in this context, as it offers a continuous source of new ideas and inspiration that can be unlocked by emerging technologies and help auditors make a greater impact on the organization.

Endnotes

1 Institute of Internal Auditors, Global Technology Audit Guide (GTAG) 3, Continuous Auditing: Coordinating Continuous Auditing and Monitoring to Provide Continuous Assurance, 2nd Edition, https://www.theiia.org/en/content/guidance/recommended/supplemental/gtags/gtag-continuous-auditing/

2 Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 12 CFR 1026.51, “Ability to Pay,” Regulation Z, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/rules-policy/regulations/1026/51/

TERRENCE CAI | CISA, CIA, CISSP, FRMs

Is an internal auditor at a digital-only bank in China. He is in charge of continuous auditing solutions and audit analytics for the bank’s lending business, including consumer and small business lending.