IT governance has become a common theme within enterprises, as made evident by the inclusion of governance as a key component of the COBIT® 2019 framework1 and the publication of innumerable articles addressing the importance of implementing in-house governance frameworks.2 However, various forms of governance are relevant when reviewing current trends.3 Cybersecurity risk management governance takes a front seat in the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0, released in late February 2024.4 A review of NIST CSF 2.0 from an agency theory perspective provides cybersecurity and governance professionals with a conceptual understanding of how governance can be extended to cybersecurity risk management.5 This level of understanding allows decision makers the opportunity to identify the potential motivation of organization members, predict where potential conflicts of interest may occur, and address cybersecurity risk management governance to reduce these issues.

Governance

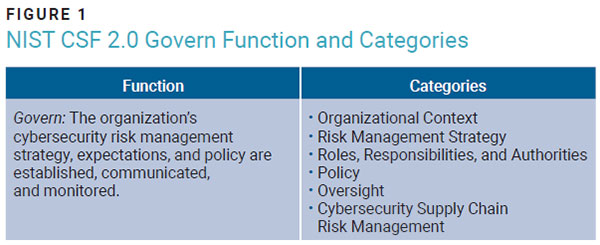

To “govern” is to conduct the policy, actions, and affairs of a state, organization, or people.6 Therefore, governing involves acting on another’s behalf with the implied intent of adding value for those being governed or those affected by the governing policies and actions. NIST CSF 2.0 (figure 1)7 elevates “govern” from an identity function category to the newest and most important function in the cybersecurity risk management framework. NIST CSF 2.0 states, “The govern function provides outcomes to inform what an organization may do to achieve and prioritize the outcomes of the other five functions in the context of mission and stakeholder expectations.”

To achieve cybersecurity risk governance, NIST CSF 2.0 lists 31 separate outcomes. Implementing policies and processes to achieve every outcome can be overwhelming for both enterprises and their staff members. One approach is to review governance from an agency theory perspective.

Agency Theory and Cybersecurity Risk Management

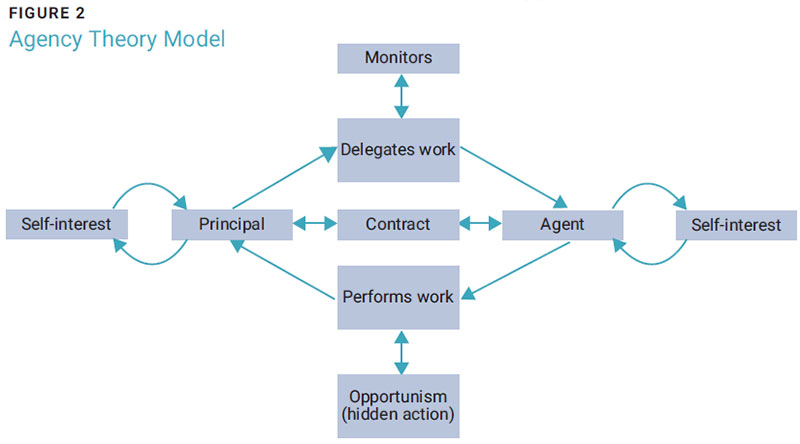

At the core of agency theory is the notion that one person—the agent—acts on behalf of another person or enterprise—the principal. The principal has self-interests but needs the agent to perform actions because of the principal’s limited capacity, regulations, or common practice. Examples include employees (agents) working for the enterprise’s owner or founder (principal), a lawyer (agent) representing a client (principal), and a real estate agent listing a home for a seller (principal). The agent in the case of cybersecurity risk management is likely to be the chief information security officer (CISO), but the agent can be anyone inside the enterprise acting on its behalf.

A problem with the principal-agent relationship is that the agent also has self-interests. These interests often cause the agent to perform actions that are beneficial to both the principal and the agent or, if the opportunity exists, to perform hidden actions that benefit only the agent.

Decades of agency theory research show that the best-maintained principal-agent relationships are governed by formal contracts whereby the principal delegates specific tasks and then monitors the agent’s actions.

A problem with the principal-agent relationship is that the agent also has self-interests. These interests often cause the agent to perform actions that are beneficial to both the principal and the agent or, if the opportunity exists, to perform hidden actions that benefit only the agent.A complete agency theory model is developed when all these concepts are combined (figure 2).

The agent’s actions can add risk for the principal if the agent does not understand the principal’s interests, lacks the capacity to complete the delegated tasks, or acts in the agent’s own self-interest. These elements are enhanced in enterprises where there are multiple layers of principals and agents. Figure 3 illustrates how the board of directors (BoD) is the agent for the enterprise while simultaneously serving as the principal for the chief executive officer (CEO). The BoD has self-interests, and it is possible for the board to relay information, make contracts, or delegate actions to the CEO that are not in the enterprise’s best interest. Every additional layer of organizational structure adds opportunities for miscommunication or hidden agent actions.

A review of cybersecurity risk management from an agency theory perspective identifies three potential scenarios that may cause the agent to make decisions that are not beneficial to the enterprise.

Scenario 1—Lack of Information

The structures of some enterprises do not give the agent access to all the information necessary to make the best risk management decisions. Figure 2 shows how important it is for the principal (the enterprise) to determine its self-interests, develop contracts with its agents (CISO or other manager), delegate work, and then monitor the results. However, in many cases the agent does not fully understand the principal’s interests. This lack of understanding may be because the enterprise does not fully understand its own interests, the agent is not present when the principal is discussing or deciding issues that guide the principal’s interests, or the agent is embedded in the organizational structure and receives misinformation about the principal’s interests.

The Equifax security breach in 2017 was at least partially due to these types of issues. Congressional investigations revealed that prior to 2005, Equifax’s organizational structure had the chief security officer (CSO) reporting to the chief information officer (CIO), who reported to the CEO, who reported to the BoD.7 However, interpersonal conflicts between the CIO and CSO caused the CSO to be reassigned, reporting to the chief legal officer instead. This move created a situation in which the CSO was receiving information about Equifax’s interests from someone who was not familiar with cyberrisk and had different self-interests.

Organizations can strengthen their cybersecurity governance by creating organizational structures that ensure that the agent managing cybersecurity risk fully understands the principal’s interests and is present when the principal is making decisions that may affect cybersecurity risk. The NIST 2.0 Roles, Responsibilities, and Authorities section can be useful in further organizing thoughts about organization structure.

Scenario 2—Lack of Resources

The top two reasons enterprises do not complete cyberrisk assessments are time commitments and a lack of qualified personnel.8 Agency theory shows the need for contracts between agents and principals, but good contracts require significant negotiations between the parties. The principal states the desired outcomes, the agent informs the principal what resources are needed, the agent performs the work, and the principal monitors the results. Organizational risk is created when there are inadequate resources to perform each of these tasks.

The 2017 Equifax breach provides an example. An email from the Apache Software Foundation reported the vulnerability Apache Struts CVE-2017-5638 on 7 March. Two days later, an internal Equifax email instructed IT administrators to patch the vulnerability. However, the information security department decided to run security scans instead of installing the patch, and the scans did not identify the vulnerability.9 This breach illustrates that even direct delegation of specific actions by the principal can lead to different actions by the agent. This scenario shows how important it is for the principal to monitor the agent’s actions. Strong cybersecurity governance must include consistent monitoring. This is not intended to be a form of micromanagement, but to establish policies and procedures where each member (principal or agent) is vigilant about holding the other members accountable for abiding by policies and directives. Strong contracts (policies) are only effective when members ensure that they are maintained.

Organizations can reduce cybersecurity risk by incorporating strong contracts between principals and agents and by monitoring these actions. The NIST 2.0 Policy and Oversight sections provide further information in these areas.

Scenario 3—Agent’s Self-Interest

Agents’ self-interests can affect their actions. Agents may perform hidden tasks that fulfill their own self-interests but harm the principal. However, the CISO is not the enterprise’s only agent. Based on the organizational structure, the CISO may answer to a myriad of other managers, each of whom is a principal (to the CISO) and an agent (to the manager’s supervisor). Every management layer therefore has a principal-agent relationship, and self-interests can lead to hidden actions that increase organizational cybersecurity risk.

Another example from the Equifax breach shows the effects of self-interest. The information security department’s decision to run security scans instead of installing the patch was based on self-interest.10 Similarly, three senior Equifax executives sold US$1.8 million in stocks on 1 and 2 August and did not inform the public of the breach until 7 September.11 Agents’ propensity to fulfill their own self-interests emphasizes the need to delegate specific actions and to monitor those actions.

Organizations can address this issue by evaluating the actions of their staff members to ensure that each member is considering the effect of their actions on the other staff members. Developing a practice of discussing the impact of individual actions on the organization’s cybersecurity risk during board meetings and key organizational events can help staff members see the importance of each member’s actions in cybersecurity risk management governance.

Using Agency Theory Concepts to Guide Cybersecurity Governance

The NIST CSF 2.0 governance function can be analyzed from an agency theory perspective to help enterprises develop policies and take actions that ensure the proper management of cybersecurity risk. Each of the six NIST CSF 2.0 governance categories is examined in terms of how to attain cybersecurity risk governance.

Organizational Context

“The circumstances—mission, stakeholder expectations, dependencies, and legal, regulatory, and contractual requirements—surrounding the organization’s cybersecurity risk management decisions are understood.”12

It is unfair for an enterprise to employ an agent if it does not know exactly what it wants the agent to accomplish. Enterprises must therefore take the time to determine their self-interests, along with the interests of those they are serving as agents. This is perhaps the most difficult part of cybersecurity risk management governance because it requires the enterprise to consider how each participant’s actions will affect the entire system’s security.

These discussions should be held at the highest organizational level possible and should include:

- Services and capabilities required to meet the mission

- Legal, regulatory, and contractual cybersecurity requirements

- Customers’ needs and expectations that could be affected by cybersecurity

Risk Management Strategy

“The organization’s priorities, constraints, risk tolerance and appetite statements, and assumptions are established, communicated, and used to support operational risk decisions.”13

The development of a risk management strategy is an extension of the organizational context function and should include top-level members of the enterprise. The first discussion should go beyond self-interests and determine the enterprise’s (the principal’s)—not the CEO’s or CIO’s (the agent’s)—risk appetite. Participants in these discussions should determine what is best for the enterprise as a whole and develop a risk management strategy that protects the enterprise’s self-interests. This strategy also prioritizes how organizational resources will be allocated.

A critical step in determining risk appetite is to consider different cybersecurity-related metrics. This process helps organizational leaders determine which metrics best define the enterprise’s self-interests. Understanding why these metrics were chosen helps organizational leaders become better agents for the enterprise.

Roles, Responsibilities, and Authorities

“Cybersecurity roles, responsibilities, and authorities to foster accountability, performance assessment, and continuous improvement are established and communicated.”14

The organizational structure can be seen as a daisy chain of principals supported by agents who are, in turn, principals for other agents. The CEO is the BoD’s agent and takes action on behalf of the board. Similarly, the CEO is a principal supported by many other agents (e.g., CIO, chief financial officer [CFO]). Every principal-agent relationship increases the likelihood of an agent taking hidden actions based on the agent’s self-interests or an agent acting without the necessary resources or information. Each layer increases cybersecurity risk to the enterprise. Discussions about who is responsible (the agent) for implementing the cybersecurity risk management strategy should involve organizational leaders and include formal discussions about the principal-agent relationship. Determining to whom the agent reports is crucial and should include consideration of who is best situated to ensure that the enterprise’s self-interests are met.

After determining who will be the cybersecurity risk management agent, it is time to determine the agent’s responsibilities. The formal contract between the principal and the agent is negotiated at this point. What is expected of the agent and what resources will be provided by the principal should be discussed. Again, the enterprise’s leadership team must keep in mind that the enterprise’s self-interests are paramount.

Similarly, the leadership team should consider organizational structures or assignments that might put agents in the position of having self-interests that compete with those of the principal. Analyzing the organizational structure through the agency theory lens allows enterprises to create organizational structures and policies that ensure that agents’ self-interests are identified, monitored, and minimized.

Policy

“Organizational policy is established, communicated, and enforced.”15

Research has shown that in the best principal-agent relationships, the principal delegates detailed work assignments to the agent. It is impossible to anticipate every specific action related to cybersecurity risk management governance that must be accomplished by the agent, so policies must be developed to guide the overall actions of agents. These policies should serve as general directions that the agent understands at the conceptual level.

In addition, these policies should cover a range of potential situations. The leadership team should prioritize situations and designate which items must be completed and which ones should be completed, as well as the conditions under which actions should be taken. This can be a painstaking process, but governance is not easy. It takes time to prioritize and determine how best to serve the enterprise’s self-interests.

Oversight

“Results of organization-wide cybersecurity risk management activities and performance are used to inform, improve, and adjust the risk management strategy.”16

The principal cannot track what it does not measure, and it cannot expect the agent to always have the principal’s self-interests in mind if it does not review and monitor the agent’s actions. Monitoring leads to open discussion between the principal and agent about what can and cannot be achieved in the current environment. Monitoring should therefore be a communication link between the principal and the agent, with regular discussions about how the changing cybersecurity environment, lack of information, or lack of resources is affecting the agent’s ability to meet the objectives and metrics of the risk management strategy.

Cybersecurity Supply Chain Risk Management

“Cyber supply chain risk management processes are identified, established, managed, monitored, and improved by organizational stakeholders.”17

Principal-agent relationships also exist whenever one enterprise acts on behalf of another. This is evident in NIST CSF 2.0, which added cybersecurity supply chain management as a new category. There is considerable cybersecurity risk in every external relationship. In some cases, one enterprise acts as the agent for another enterprise. In other cases, the enterprise is the principal. Each of these relationships involves organizational self-interests that may not be in alignment. Similarly, the parties’ risk appetites will likely not be the same. Each of these relationships requires organizational leaders to consider how the other enterprise affects their cybersecurity risk. Developing contracts, delegating work, and monitoring actions are necessary steps to ensure that the principal’s self-interests are met.

Conclusion

Cybersecurity risk management governance should be a high priority in today’s environment. This is witnessed by the elevated importance external agencies place on incorporating risk management governance into their frameworks.

However, the process of developing a cybersecurity risk management strategy, establishing policies, outlining roles and responsibilities, and changing the organizational structure may seem daunting. Taking an agency theory approach allows enterprises to have open dialogues, using a common language, and to make these risk-management decisions based on conceptual understandings.

NIST CSF 2.0 can help organizations with managing some of these concerns. When deciding on an organizational structure, it is important to view each individual as an independent agent. Similarly, each principal should have the tools necessary to monitor the activities of the agents, and agents should not have conflicting responsibilities. With this in mind, organizations might start to question structures wherein the CISO reports to the CIO. An alternative, from an agency perspective, is to have the CISO report directly to the CEO.

Similarly, organizations should strive to make cybersecurity governance accountability a key aspect of organizational culture. Policies, procedures, and direct work orders are only effective if organization members adhere to them. Creating a culture of accountability prompts even the most junior staff member to feel empowered to question why a procedure was not followed. These actions therefore help reduce the opportunity for agents to act on self-interest instead of the organization’s interest. Incorporating the conceptual understanding of agency theory with the NIST CSF 2.0 framework may be a reasonable way to start making these adjustments and ultimately decrease cybersecurity risk through strong governance.

Endnotes

1 ISACA®, “COBIT 2019 Framework: Introduction and Methodology,” https://store.isaca.org/s/store#/store/browse/detail/a2S4w000004Ko9cEAC

2 Wilkin, C. L.; Chenhall, R. H.; “Information Technology Governance: Reflections on the Past and Future Directions,” Journal of Information Systems, 2020, https://publications.aaahq.org/jis/article-abstract/ 34/2/257/1179/Information-Technology- Governance-Reflections-on?redirectedFrom=fulltext

3 Pearce, G.; “Five Things for Governance Professionals to Put on Their 2024 To-Do List,” ISACA, 15 December 2023, https://www.isaca.org/resources/news-and-trends/isaca-now-blog/2023/five-things-for-governance-professionals-to-put-on-their-2024-to-do-list

4 National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), “The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0,” USA, 26 February 2024, https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.CSWP.29

5 Cyert, R. M.; March, J. G.; A Behavioral Theory of the Firm, Prentice Hall, USA, 1963

6 Oxford English Dictionary, https://www.oed.com/

7 EPIC, “Equifax Data Breach,” 2017, https://archive.epic.org/privacy/data-breach/equifax/#:~:text=The%202017%20Equifax%20Breach&text=The%20company%20stated%20that%20the,Names

8 ISACA, State of Cybersecurity 2023 Global Update on Workforce Efforts, Resources and Cyberoperations, 2023, https://www.isaca.org/state-of-cybersecurity-2023

9 EPIC, “Equifax Data Breach”

10 EPIC, “Equifax Data Breach”

11 EPIC, “Equifax Data Breach”

12 NIST, “NIST CSF 2.0”

13 NIST, “NIST CSF 2.0”

14 NIST, “NIST CSF 2.0”

15 NIST, “NIST CSF 2.0”

16 NIST, “NIST CSF 2.0”

17 NIST, “NIST CSF 2.0”

GERALD F. BURCH | PH.D.

Is an assistant professor at the University of Florida (Pensacola, Florida, USA). He teaches courses in information systems and business analytics at both the graduate and undergraduate levels. His research has been published in the ISACA® Journal and several other leading peer-reviewed journals. He has helped more than 100 enterprises with his strategic management consulting and can be reached at gburch@uwf.edu.

JORDAN BURCH

Is the chief technology officer at Foster Care to Success, where his focus is monitoring system availability, logging system event data, and reporting. He has implemented monitoring platforms for both the private and public sectors, including entire state digital infrastructures and international pharmaceutical and agricultural ventures. Burch has a strong background in network engineering and the difficulties faced by large enterprises attempting to collect usable system statistics from the far reaches of their infrastructures. He is involved in projects related to the Internet of Things, wherein he collects data from embedded systems that allow greater visibility of environmental factors at a much larger scale. He can be reached at https://www.linkedin.com/in/jordanburch/.

MIKE MCGARRY

Is an information systems instructor at Virginia Commonwealth University (Richmond, Virginia, USA). He conducts research related to the economic analysis of cybersecurity. He has more than 30 years of experience and was the chief information officer of a Fortune 300 company when he retired from the industry.